One last trip outside Istanbul: Nevşehir and Kırşehir

Only a few weeks ago I was on a gastronomy trip to the Central Anatolian provinces of Nevşehir and Kırşehir with a group of Lebanese food and travel writers and our excellent Turkish guide who curated everything. That trip now is seared in my mind as one of the last I might take for a very long time.

Looking at horizon from a high point above Göreme, one cans see breathtaking ridges, colors and shapes (namely the region's iconic fairy chimneys) that only could have been made by Mother Nature. Below are earth-colored houses, a stable of horses, flocks of sparrows, and mockingbirds dive-bombing down the hill before zooming back up again. The weather was unseasonably warm for early March in Cappadocia, and everything was so beautiful it filled you with a sense of gratitude just for being present and alive.

Though this was only a few weeks ago, the moment feels impossibly distant.

The coronavirus already dominated the world’s agenda. Yet the first case had not yet been confirmed in Turkey. Life here continued as normal, though people working in the local tourism sector were already expressing worries about the impact of the virus.

I was on a gastronomy trip to the Central Anatolian provinces of Nevşehir and Kırşehir with a group of Lebanese food and travel writers and our excellent Turkish guide who curated everything. We started off the morning with cheese-stuffed bazlama and tea, before going to Dibek, a traditional restaurant that serves testi kebabı, lamb that is slow cooked in a clay pot for several hours before being cracked open and served alongside a variety of spices and pickles. This dish can be found in Istanbul, but many of the places making it are tourist traps while Dibek, located in the dead center of Göreme, is the real deal.

Our next stop was Cappadocia University, where chefs Cem Aydoğu and Melih İçigen, also both instructors at the school, prepared us the delicious, complex dish mutancana, a classic Ottoman-era configuration consisting of braised lamb cooked in bone broth and topped with a variety of dried fruits and nuts, a signature style of the Empire's cooking. We were also served a lovely chard-flecked soup and a simple but mouthwatering meze based around roast eggplant, yogurt and strips of red pepper.

After that was a tasting at Kocabağ winery, where proprietor Memduh bey, whose family has run the place for decades and who instantly strikes you as someone who knows their wine, served as an array of his excellent reds and roses, some of which were sourced from the grape kalecik karası, which is indigenous to the region. Cappadocia is known as one of the country's premiere wine regions, and Memduh bey explained the secret: due to the extremities in temperature in the area, the roots of the grape vines seek shelter as deep in the ground as they can, absorbing the earth's minerals in the process, giving the edge to the special grapes that bloom as a result.

After being too stuffed to have a proper dinner, we sampled some more regional wine back in Göreme alongside a cheese plate and bowls of rich eggplant soup, and called it a night. The next day, were headed to Kırşehir, just an hour away from Nevşehir, though the latter province, due its location amid many of Cappadocia's most famous sights, gets much more attention than the former.

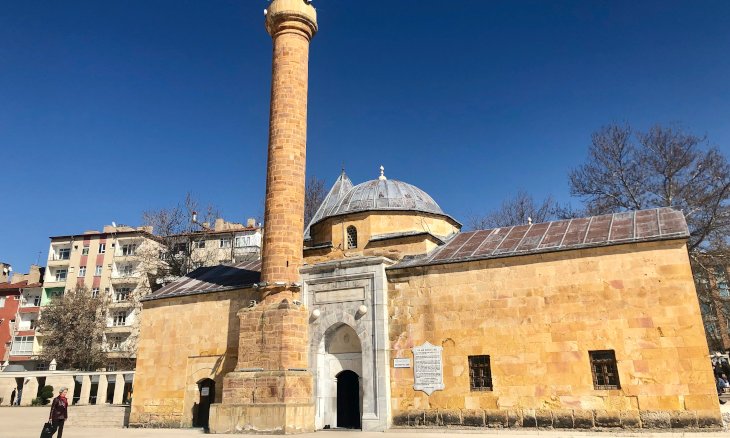

Kırşehir is a pleasant and lively if unremarkable city, though not devoid of grand monuments, including the sandy, stone-built mosque and tomb complex of the influential 13th century religious leader Ahi Evran. We were unfortunately unable to see the Seljuk-era Cacabey Madrasa, it was fully covered by corrugated metal fencing as it is currently undergoing restoration, but based on the photos it alone looks like enough of an excuse to stop in Kırşehir.

But the better reason is the region's remarkably excellent cuisine, which we feasted on at a restaurant run by the city, where two women who were absolute masters at their crafts served us a variety of local dishes and proudly explained how they were cooked and what ingredients were used. I enjoyed easily the best biber dolması (stuffed peppers) I've ever had, which were made with the green dried Cemele peppers that are endemic to Kırşehir, and are spectacularly spicy.

We were joined by Eyüp Temur, an affable gentleman who is also the deputy manager of Kırşehir's provincial culture and tourism department and a retired schoolteacher. He lamented the fact that Nevşehir and Cappadocia benefitted from so much tourism while Kırşehir, despite its close proximity, is largely ignored.

“They come to Nevşehir by plane, they travel around Cappadocia, and return to Istanbul with the same flight. This is a problem for us in terms of tourism,” Temur said, adding that Kırşehir was home to rich historical, cultural, and thermal tourism. He didn't have to convince me as I always already sold based on the meal we just had.

The city is perhaps best known as the birthplace of Neşet Ertaş, one of the most beloved musicians in modern Turkish history, a true folk legend. He passed away in 2012, and the city built a museum in the memory of Ertaş and his father Muharrem, also an iconic folk musician. In one room, a stunningly realistic clay statue of Ertaş was perched on a chair, outfitted in clothes that once belonged to the man himself, clutching his dear bağlama in hand. The statue came to life with its hand moving across the bağlama's fret board as one of Ertaş' classics played in the background. Ertaş is so influential that despite his penchant for deeply melancholy ballads, he also directly inspired the style of bombastic, electrified folk that is played in the famous nightclubs of Turkey's capital.

While Temur and his colleagues are actively trying to increase the numbers of tourists coming to Kırşehir, unfortunately the timing could not have been worse. With coronavirus having functionally stopped life as we know it in its tracks, Kırşehir's tourism priorities have likely been pushed to the back of the agenda.

Upon return to Nevşehir, we were treated to an elegant, special multi-course dinner curated by chefs Aydoğdu and İçigen at restaurant Lokal Sinasos in the picturesque village of Mustafapaşa (Sinasos was the old Greek name of the town). The chefs whipped up a stunning array of dishes that were deliberately sourced from and inspired by local and seasonal ingredients, including picturesque pumpkin blossoms stuffed with rice and served with a tangy yogurt mint sauce, and a dish of Jerusalem artichokes and lentils in olive oil, lightly topped with chopped parsley, and a sumptuous lamb shank served alongside a chunk of the famous local potatoes, succulent mushrooms and several whole cloves of pungent roasted garlic that I gobbled up without shame.

Our group's conversations was peppered with discussions of the ominous coronavirus, but Turkey was still going about business as usual, and it wasn't difficult to put it in the back of our minds amid the unparalleled surroundings. But just under a month later, that trip now is seared in my mind as one of the last I might take for a very long time. May the all the wonderful people I met on this trip and everyone in the region be blessed with good health and may this difficult, unfathomable period pass sooner than later.