Istanbul's Tozkoparan neighborhood residents win eviction case but expect fight to be ongoing

Homeowners across Istanbul, including the Tozkoparan neighborhood, are uniting against the city's urban renewal project, which the government says are meant to increase the city's resistance to earthquakes. But the project may leave many residents, like 70-year-old Ayşe Yılmaz, out in the cold.

Naomi Cohen / Duvar English

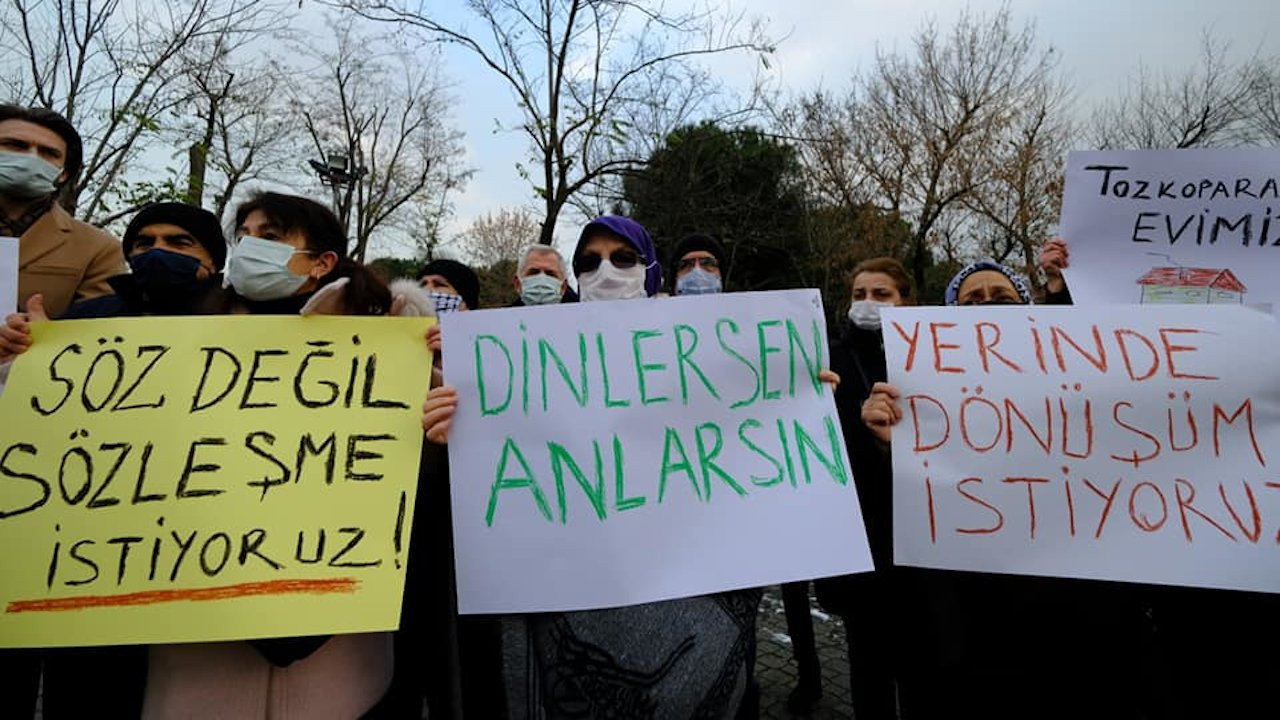

70-year-old Ayşe Yılmaz defied curfew earlier this month in order to spend an hour in the cold waiting for good news. It was mid-day, so the 150 other people gathered in Barış Park in the Tozkoparan neighborhood of Istanbul were mostly housewives and retired people.

Yılmaz, who asked to use a pseudonym, was expecting the city to cut her electricity, water, and natural gas within days via a plan to demolish her building, and 301 others, in order to build ones more resistant to earthquakes.

The septuagenarian owns her apartment, but would be required to pay for a remodeled one in the new building. With only enough money to sustain her for the next two months because of medical bills for her cancer treatment, Yılmaz says she will not budge from her home.

“When we moved in, this place was a dump,” she said. “But we stayed.” Her apartment faces the park, one of the many green spaces in Tozkoparan, but a rarity in other parts of Istanbul.

After her sons moved out, Yılmaz took in two renters, but they accepted the 3,000 TL to move out of the building (roughly equivalent to one month’s minimum wage) that the Güngören municipality is giving out.

One of her sons bought an apartment a short walk from the park in a building in comparatively worse condition, so Yılmaz is asking why her block is the one slated for the first phase of demolition.

On Jan. 15, three weeks after receiving an eviction order, Yılmaz got the news she was hoping for. The local administrative court ruled in favor of the 31 residents who filed cases and cancelled the emergency evacuation.

However, when the neighbors gathered in the evening to celebrate, they were reminded that the case could be appealed to a higher court and that there are 21 cases still pending to stop the urban renewal project.

The fight against urban renewal continues

“We’re in training,” joked Ömer Kiriş, the head of the Tozkoparan Association (TOZDER), the front for residents who oppose the construction project. TOZDER has been filing cases since 2008, when the city first tried razing Tozkoparan.

Since then, TOZDER has joined dozens of other neighborhoods in Istanbul in resisting urban renewal projects. The Tozkoparan project alone costs an estimated 700 million Turkish liras. The projects are all at different stages, but the Minister of the Environment and Urban Planning said, one week after the eviction orders went out, that Tozkoparan would serve as an example for other urban renewal projects across the city.

“They brought in experts this time to get the job done,” said Kiriş. Istanbul's mayor Ekrem Imamoğlu from the opposition Republican People's Party (CHP) campaigned in Tozkoparan in 2019 promising a fair solution, but never came back.

Now the AK Party-controlled Güngören municipality has hired a team prepared to defy court orders, said Kiriş. The AKP greets residents at their local urban renewal office. Outside, a truck serves soup to those who wander in. The municipality also hung banners on every other street announcing the sum of money that homeowners are promised if they sign the deed of consent. Most have not signed.

Most residents are not against renewal

Unlike other neighborhoods, Tozkoparan has reached near consensus about the project, which one speaker at Barış Park said is remarkable considering efforts to divide the residents.

The houses in the neighborhood tend to be small and in disrepair, so most residents are not against renewal; they just want to have their say in the planning, have their houses kept at an affordable price, and have evictions organized according to need. None of the demands have been met.

Instead, the deed of consent, which was drafted without consulting the residents, sets above-market prices for the new higher-quality apartments, before inflation and interest are added.

TOKI, the national housing development administration that is heading the project also plans to build schools, offices, and shops, all well-connected to Istanbul's major transportation lines.

More about gentrification than disaster preparedness.

Members of TOZDER argue that the project seems to be more about gentrification than disaster preparedness. They point out that many of the buildings marked 'at-risk' were found to be safe in other studies. To Kiriş, TOKI is using Tozkoparan to chase financing from big investors and secure profits while few sectors are growing.

“There’s a neighborhood culture that you can’t find anywhere else in Istanbul, and they’re trying to tear it down,” said Serap Taşkın, a younger resident who grew up in Tozkoparan.

The first apartments were built in the 1960’s as social housing for workers in nearby factories. Those factories are now gone, but many of the families have stayed. Some bought their homes early on; others, like Esma Demir, have been trying to buy for the past 15 years, but have been unable to petition the project developers to count their rental payments toward a purchase.

Renters are 'left with no choice'

Renters like Demir and homeowners like Yılmaz may refuse to leave, but many worry that their electricity, water, and gas could be cut any day.

Durmuş Murtezaoğlu, who has lived in Tozkoparan for 41 years, said he cannot live without utilities during a pandemic in the middle of winter. He signed the deed of consent (now called a contract) that affords him 1,500 Turkish liras in rent support for five months. But the costs just to find and secure a new apartment already surpass that amount.

“I’ve taken on a huge burden,” said Murtezaoğlu, adding that he didn’t want to sign but was left with no choice. “The state is punishing us and making us suffer by doing it this way. It doesn't have to be like this.”