The Islanders of Mare Nostrum*, ECHR and unfreedom of expression

Tolga Şirin writes: We are witnessing a downfall of the ECHR in Turkish public opinion. The problematic conduct of formal relations with Ankara is not the only reason for that. This also has to do with some recent controversial judgements. One example is the Court's March 2020 judgement on the Altıntaş Case which had symbolic importance for the left-wing opposition in Turkey as it had to do with famous 1968 generation leader Mahir Çayan. The Court's judgement contradicted both its ongoing case-law and the reality of Turkish political fora.

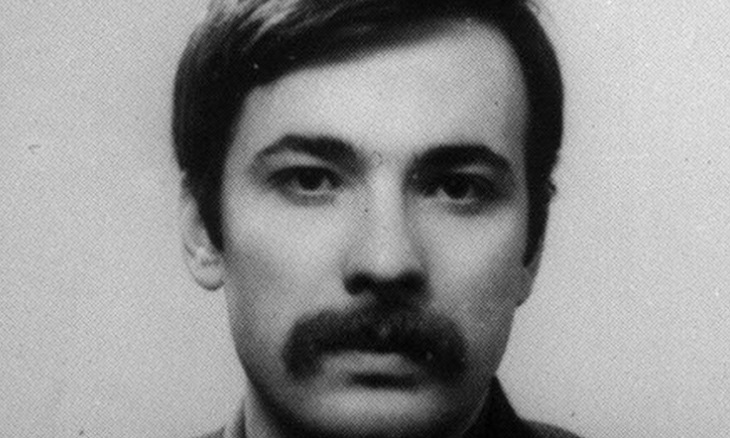

Tolga Şirin

Last month we wrote a blog post regarding the symbolic downfall of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in Turkish public opinion. The problematic conduct of formal relations wasn’t the only reason for that. This had also to do with controversial judgements the Court made.

The problematic judgments of the Court only further contribute to this symbolic collapse. In this piece, I would like to focus on one of the many examples in this regard the Altıntaş v. Turkey that was delivered in March 2020.

The case had particular and symbolic importance for the left-wing opposition in Turkey as it had to do with Mahir Çayan, one of the famous leaders of the 1968 generation in Turkey.

Before dealing with the case, some information should be provided about the background of the issue. The youth of the 1968 generation in Turkey - just as in other countries of the third world - embarked on a revolutionary struggle inspired by Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh and Cuba’s Ernesto Che Guevara. According to them, Turkey had become a semi-colony of the United States. Therefore, a second “War of Independence” had to be fought. Their motto was “Fully independent Turkey!” Undoubtedly, the struggle was more challenging in the middle eastern Turkey than in western countries. Their struggles, which began with university boycotts, mass demonstrations, and calls for a strike, gradually shifted towards “urban guerrilla” tactics inspired by the “foco” theory.

Yet the government back then was terribly cruel towards these young people. After the military coup of 1971, three university students Deniz Gezmiş, Yusuf Arslan, and Hüseyin İnan were sentenced to death for “attempting to change the constitutional order”, though their actions did had not injured nor killed anyone. In fact, it was the response of right-wing soldiers against the left-wing military intervention that had occurred about a decade ago in 1961 and their socialist rivals within the military. The military government executed three conservative politicians (Prime Minister Adnan Menderes and ministers Hasan Polatkan and Fatin Rüştü Zorlu) in 1961. When it came to 1972, the right-wing factions of the military retaliated. Still, nowadays, a consensus prevails amongst most left and right wing politicians, regarding both events as black stains in Turkish history.

One of the interesting highlights in this period was the actions of Mahir Çayan and that of his friends. They kidnapped three technicians working at the NATO military base in Turkey and went to Kızıldere, a village of Tokat, in order to prevent the execution of death penalties by negotiating, and to show solidarity with their comrades (Deniz Gezmiş and his friends). But the response of the security forces was too harsh. The security forces carried out an operation that was incompatible with the Court’s current criterion concerning the right to life. As a result of the security forces’ operation, everyone in the house died, except for Ertuğrul Kürkçü, who later worked as a consultant for Human Rights Watch and became the editor of the Independent Communication Network (BiaNet). As of today, Kürkçü is the incumbent Honorary Chairman of the People's Democratic Party (HDP) and Honorary Associate of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE).

The Altıntaş Case

The applicant Cihan Altıntaş was the editor of the local monthly periodical Tokat Demokrat distributed in Tokat, a small city of Turkey. An article on the events in Kızıldere was published in the March 2007 issue of the applicant’s periodical. The article in question, entitled “Mahir and His Friends Still Live Like Youth Idols” read as follows:

“On March 30, 1972, a group of young revolutionaries were [massacred] in the village of Kızıldere in Tokat. Mahir Çayan and his friends, who wanted to prevent Deniz Gezmiş and his friends’ execution, kidnapped the technicians at an English base in Ünye. They sought to stop their friends’ execution, Deniz Gezmiş, Hüseyin İnan, and Yusuf Arslan, but they were slaughtered without achieving [their goal]. Mahir and his friends live on as youth idols.”

The criminal court charged the applicant with the offense of condoning the crime and the criminal. It considered that “the article in question, in particular by the use of expressions such as ‘massacred’ and ‘youth idols’ defended Mahir Çayan, who had committed offenses by his participation in several illegal acts and who was ultimately killed in an armed clash between him and the state security forces, as well as his efforts and behaviour aimed at saving people tried and sentenced to death by courts empowered by the Constitution.” The decision became final in domestic law.

When the case was brought to Strasbourg, the Court found that the assessment of national authorities’ was in accordance with the Convention. Firstly, the Court noted that the kidnapping committed by Mahir Çayan and his friends and their response to the security forces in Kızıldere were violent acts. This is somewhat understandable. However, the interesting point was that the Court agreed on describing what happened in Kızıldere, as a “massacre” and presenting “Mahir Çayan and his friends” as “youth idols” may encourage some young people (especially members or sympathizers of some illegal organizations) to commit similar acts of violence.

For me, it was not only a strained interpretation but also contradicting both its ongoing case-law and the reality of Turkish political fora.

Tense Context?

For the Court in Altıntaş, the memorial ceremonies for Mahir Çayan and his friends had a strained social context. It was not only ironic but also the proof that the eyes looking at Turkey from Strasbourg, could not fathom the social facts and political developments there.

In the judgment, the Court found that leftist groups took action every year on March 30, when the Kızıldere incident took place. This is a valid observation, but these commemorations are not marginal, as implied in the Court’s judgment. Their commemorations took place even under the roof of the Parliament. For instance, ÖDP member Ufuk Uras in 2012, HDP member Ertuğrul Kürkçü (the only socialist surviving in Kızıldere) in 2012, and the main opposition party CHP member Hilmi Yarayıcı in 2016, commemorated Mahir Çayan and his friends on their death anniversary, the 30th of March. What is more interesting is that Ayşenur Bahçekapılı, the parliamentary speaker of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2018, said, “I also respectfully commemorate Mahir Çayan and his friends who were killed on March 30.” The statement of Bahçekapılı was not surprising. Because right-wing / Islamist circles have been honoring Deniz Gezmiş and Mahir Çayan for their anti-imperialist struggle for a while. Even right-wing parties criticize today’s left parties for deviating from Deniz Gezmiş and Mahir Çayan’s stance. On the other hand, it is still in public memory that President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan shed tears (a part of a propaganda strategy according to some) for the leftist youth who were executed in the 1970s, in a speech just before the 2010 constitutional amendment. Therefore, unlike the Court's assumption, half a century later, neither Gezmiş’s nor Mahir’s commemoration ceremonies in Turkey trigger any tension.

The situation is no different for the Turkish public. A well-known example of this, is an episode (nr. 57) of the popular, prime time Turkish TV series called “Remember Dear” (Hatırla Sevgili), in which, Mahir Çayan and the Kızıldere incident was the main theme. In the series, this incident was presented with a narrative highlighting that the anti-imperialist youth even dared to die for their ideals, while protagonists were introduced with sympathy. That episode of the series did not receive any adverse reactions and was watched by a record number of people.

Moreover, today, anyone can easily find five to ten books about Mahir Çayan in any bookstore in Turkey. So, Mahir Çayan and his friends are no longer a taboo.

The Case-Law on Incitement to Violence

Altıntaş was incompatible with the Court’s settled case law on incitement to violence in two respects.

First, the applicant’s political engagement, the local newspaper’s nature in which the article was published, and the target audience were not considered. However, the Court would have pointed out these points in numerous decisions in the past.

Second, the fact that the Court confirmed the imposition of sanctions on a journalist for saying “Mahir Çayan and his friends” are “youth idols” and using the phrase “massacres”, was a rejection of its established case-law. The applications of many people who described an operation conducted by security forces as a “massacre”, received by the Court, especially in the context of the ongoing and tense Kurdish question. In these decisions, the Court concluded that no sanctions could be imposed for these kinds of statements unless incitement to violence and relevant and sufficient justification was provided (see e. g. inter alia Ceylan, Arslan, Sürek and Özdemir, Karataş). On the other hand, it was stated in dozens of different decisions that praising Abdullah Öcalan, the still-living leader of the PKK, alone could not be considered “praising the crime and the criminal” (see e. g. inter alia Kılıç and Eren; Müslüm Yalçınkaya and others; Bülent Kaya; Aktan; Aydoğan) In other words, for the Court, expressions of sympathy for a political criminal do not automatically require a penalty, even in a tense context such as the Kurdish issue.

The case-law was compatible with Turkey’s local culture, and realities as these determinations were also valid inference for “criminals” in history a fortriori. For instance, political figures such as Köroğlu and Sheikh Bedrettin, who rebelled against the government of the time, were considered as “eşkıya” in their lifetime. Debreli Hasan, who killed and was murdered for his love, was also seen as a “murderer” in his days. However, today, these people are considered as idols because they were committed to a cause, while poems and songs had been written in their honour. We do not consider these people as praising a crime and a criminal unless there is a clear call to violence. These people are even considered as folk heroes, as they paid the price for their struggle, which they believed in their hearts. It was also the passing of time that made them heroes in the eyes of the public.

The Case-Law in relation with Mahir Çayan and his friends

Another issue that makes the Altıntaş case problematic is the fact that it is incompatible with the Court’s other decisions regarding Mahir Çayan and his friends. For instance, the Court found a violation of freedom of expression in Sarıtaş and Geyik v. Turkey, where the applicants were charged and sentenced to ten months’ of imprisonment for disseminating propaganda in favor of an illegal armed organization, due to chanting the following slogans during a concert: “Mahir, Hüseyin, Ulaş; Fight until emancipation” (“Mahir, Hüseyin, Ulaş; Kurtuluşa kadar savaş”); “Martyrs of the revolution are immortal” (“Devrim şehitleri ölümsüzdür”). These slogans referred to Mahir Çayan and his friends. The Court concluded that an interference with these expressions could not be justified.

The Court was even able to determine similar kinds of slogans with more harsh content as follows:

“The Court observes that, taken literally, some of the slogans shouted (such as ‘Political power grows out of the barrel of the gun’, ‘It is the barrel of the gun that will call into account’) had a violent tone. Nevertheless, having regard to the fact that these are well-known, stereotyped leftist slogans and that they were shouted during lawful demonstrations – which limited their potential impact on ‘national security’ and ‘public order’ – they cannot be interpreted as a call for violence or an uprising (§ 41).

When it comes to Mahir Çayan and his friends, we see that not only slogans but also poems and songs were reflected in the Strasbourg jurisprudence. Intervention against the following poem about Mahir Çayan’s friends Sinan Cemgil, Taylan Özgür, Kadir Manga, which was also composed as a song later, came before the Strasbourg organs:

“If I disseminated the information [to the four winds] / that I said that my İnan is dead / Mountains, give me back my Kadir, my Sinan / The gendarmes spread the bullets / Nurhak remained a [memorial] monument / the mountains received my salvation / Nurhak, the sun will not rise on you / The flying birds will not make nests / The blood that has been shed will not stay on the ground / We will call to account / Don't believe that the time will stay like this / The caravan will continue on its way / Sinan is dead, Taylan is born / He shouldered his gun!”

The case concerned, in particular, the 365-day suspension of the applicant company’s (Özgür Radyo) operating license on account of a song with the abovementioned lyrics which was played on air. The Radio and Television Council (RTÜK) believed that the offending song's words infringed the principles prohibiting the broadcasting of material likely to incite the population to violence, terrorism, or ethnic discrimination, and of a nature which may arouse feelings of hatred among them. Nevertheless, The Court held unanimously that there had been a violation of freedom of expression. The reason that led the court to this conclusion was as follows:

“Lyrical lament describing the death of several THKO organization members in 1971, this song undeniably takes on a political symbolism since it is intended to denounce the police. A tribute to the dead, both evocative and descriptive, it appears not only committed but conceals a particular virulence against the police. However, it must be noted that it had a marketing authorization issued by the Ministry of Culture and was therefore accessible to all over the counter. It was also broadcast nearly thirty years after the events it tends to relate: the scope of its message is therefore undeniably weakened as well as its vindictive character (§27).”

While the Court referred to the time elapsed since the events in these decisions and the changed attitude of the Ministry overtime; it did not consider these criteria in the Altıntaş.

In the Özgür Radio, it was taken into account that thirty years have passed since these events. However, despite the fact that almost half a century had passed since the incidents in the Altıntaş case, the Court did not consider it as a factor, which might affect its judgement. Moreover, the tension surrounding these events in question have even lessened in Turkish public opinion since the Özgür Radio.

As stated in the dissenting opinion of judge Bårdsen and judge Pavli, there existed no tangible explanation in the local court’s reason as to why this statement is considered a violent call. The Court tried to find a reason in this regard, almost by replacing itself the local court.

As a result, the judgement of Altıntaş, delivered five votes to two, is incompatible not only with the settled leading case-law of the Court but also with the relevant jurisprudence on this issue. Moreover, the Court has lagged behind even the human rights standards in Turkey, with this judgement.

Conclusion

Mahir Çayan and his friends are idols for some of the youth in Turkey. Whether we like it or not, this is a fact. It was expressed even under the roof of the parliament. In a democratic society, it is not acceptable for a journalist to be punished for expressing this fact.

Ascribing such a tense meaning to an event that occurred 50 years ago seems, to say the least, odd from Turkey.

This decision has left many questions: Why has such a U-turn been made about an event that took place so long ago? Furthermore, while many problems already exist in Turkey, does lowering the human rights standard in even such an easy case mean that danger bells are ringing for other hard and significant cases?

There exists some answers to these questions among public opinion in Turkey. However, it would be right not to speculate for now.

***

I want to conclude the article by recalling Judge Bonello’s criticism to the majority of the Court in his article, which he wrote for the “Essays in Honour of Nicolas Bratza”:

“The Court’s sometimes stark ‘incitement to violence’ test would have justified as necessary in a democratic society the conviction and imprisonment of the fathers of the American Revolution, of the prophets of the Italian Risorgimento and of the Hungarian patriots, of Armenians who complained about being massacred, of the liberators of Ireland, of the wartime freedom fighters of France, of the people of Algeria who took issue with those who had more sympathy for torture than for nationhood, of those whose blood soiled the Iron Curtain in 1967, of Palestinians in search of a frontier, of Libyans dying to rid their country of bandit scum. All these approved of violence, incited to it, practised it, and trusted in its escalation.”

Today, the Court has even fallen behind the level at which those criticisms were voiced. At this point, the only consolation in this judgment is the dissenting votes of the two judges.

* Mare Nostrum is used for the Mediterranean Sea in Latin and means “our sea”. The word “Deniz” means “sea” in Turkish. Poet Can Yücel has a cryptic poem about Deniz Gezmiş called Mare Nostrum (our Deniz). Mahir Çayan wrote a poem called “islanders” in prison. While “island” describes “cell” metaphorically, the “islanders” refer to the revolutionists in dungeons. Mahir Çayan and his friends are also known as “islanders” (adalılar) based on his poem.

Author:

Assoc. Prof. Tolga Şirin teaches at the Department of Constitutional Law at Marmara University's Faculty of Law.