'Return to parliamentary system won't solve all of Turkey's problems'

Former HDP co-chair Selahattin Demirtaş has said that a return to a parliamentary system is not enough to restore democracy in Turkey. The country, he writes, lacks a “culture of democracy.”

Duvar English

Selahattin Demirtaş, the imprisoned former co-chair of the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP), penned an article arguing that Turkey lacks a cultural awareness of democracy and that a return to a parliamentary system will not fix all that is broken in the country.

In his essay for news outlet Artı Gerçek, Demirtaş, who has been behind bars for nearly five years, highlights that with an opposition united in its call for a return to democracy, Turkey is in an unprecedented position in the lead-up to the 2023 election.

“What makes the next elections so important,” he writes, “is that we will head to it for the first time in our history with a desire for and the promise of democracy at the center stage. This is a beautiful and pleasing development. The costs have been heavy, but finally, the quest for democracy has become both social and political. It has become the primary agenda [item] of the opposition.”

Demirtaş, however, does not believe that this will fix the system entirely.

“I still feel uncomfortable. It still seems like something is missing, something fundamental.”

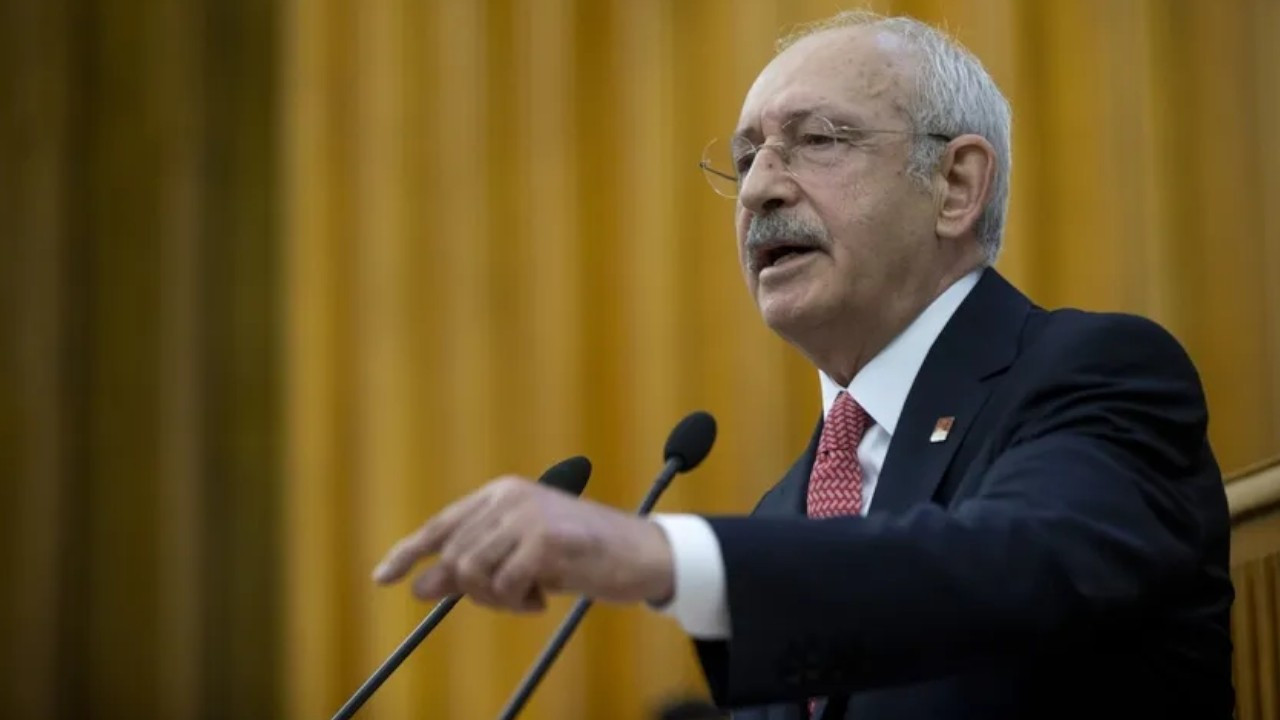

In recent months, politicians from the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the Good (İYİ) Party, along with their allies, have laid out plans for a return to a parliamentary system.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan abolished the parliamentary system in 2017 and established a presidential system in its place, giving him sweeping executive powers.

While the opposition's plans are promising, Demirtaş wrote, they are not sufficient to address the lack of democracy and democratic will in Turkey. The state cannot create democracy by itself, he argues.

“It is as if there is this belief that everything will be perfect when an enhanced parliamentary system is adopted,” he wrote, “I find this point of view extremely inadequate. I think that those who believe the problem will be solved when the state administration is partially democratized do not understand democracy at all.”

The fundamental unit of democracy is not the state, but the individual, he argues. A democratic system can only be achieved with the education and curation of the populace.

“Society and individuals can achieve [democracy] not with politics, but with education (I do not mean nationalized education, of course). With art, and literature. Democracy is not a matter of law or constitution, it is a matter of culture,” Demirtaş wrote.

He depicted the deterioration of democracy in Turkey as something that happens in all spheres, at all levels of society, not simply in politics. Without education that teaches about human rights, evolution, democracy, and objective history, he argues, you "cannot raise a democratic person."

If you can’t speak freely about women’s rights or historical traumas or the massacre of nature or exploitation in media, he writes, it doesn't matter how successful you are as an artist. If you don't implement democratic procedures in non-governmental organizations, media, universities, unions, factories and political parties, it doesn't matter whether you become a leader. And if you defend the parliamentary system while using that system to feed your own power, it doesn't matter how many votes you get, he writes.

The essay calls for Turkey to establish a culture of democracy in order for a democratic system to make a significant change. All aspects of life - not just politics - must be re-imagined in a democratic manner, Demirtaş argues.

“Democracy is a matter of culture. It is a lifestyle too serious to be stuck in the ballot box. It is a set of behaviors. Our generation will not live long enough to see democracy become a culture, a way of life. However, our generation is responsible for planting the seeds of a democratic culture in this ancient geography.”

Kurdish politician Demirtaş imprisoned for five years, counter to top European rights court rulingPolitics

Kurdish politician Demirtaş imprisoned for five years, counter to top European rights court rulingPolitics Main opposition leader calls for release of Kavala, DemirtaşPolitics

Main opposition leader calls for release of Kavala, DemirtaşPolitics Demirtaş might be released on probation in November, Turkish gov't tells Council of EuropePolitics

Demirtaş might be released on probation in November, Turkish gov't tells Council of EuropePolitics