Turkish presidential system has led to establishment of 49 new parties in three years

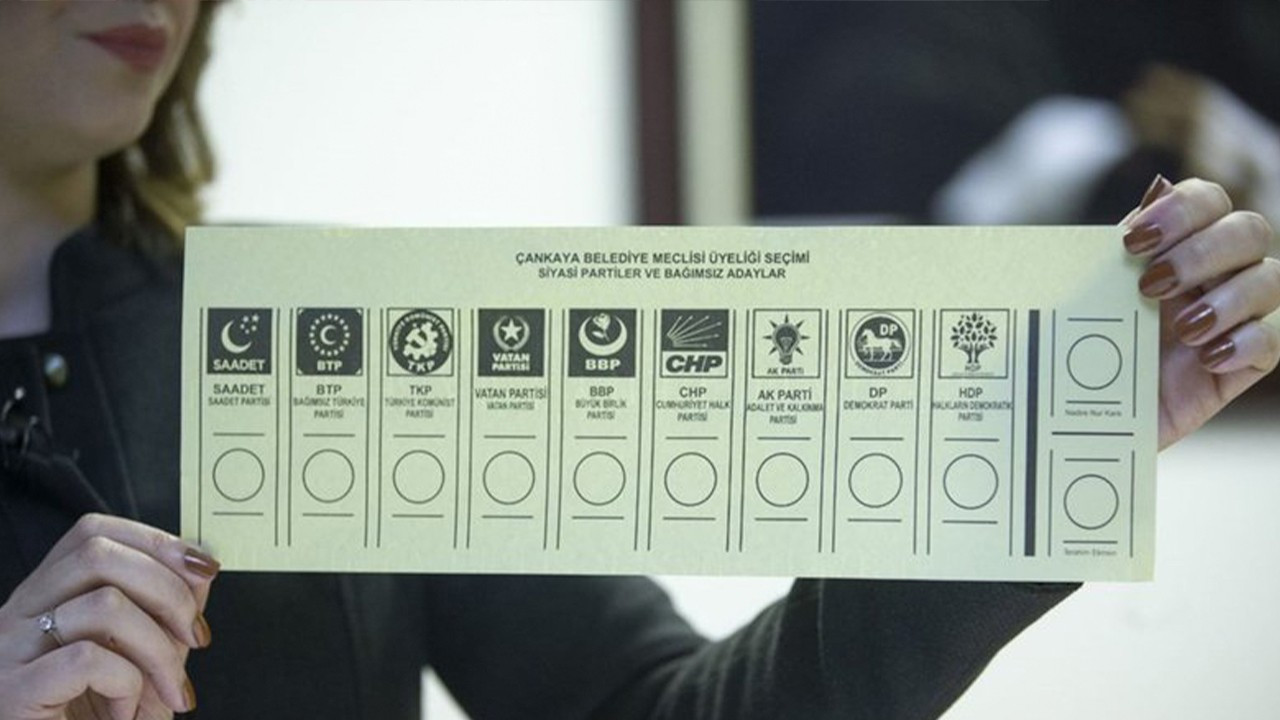

In the three and a half years since the establishment of the executive presidential system under Erdoğan and his ruling AKP, a total of 49 new parties have been established in Turkey. There is now a total of 120 parties in the country.

Müzeyyen Yüce / DUVAR

In the three and a half years since the establishment of the executive presidential system in Turkey, a record number of new parties - 49 - have been established. Experts say that this may have to do with the rise of the coalition system, whereby an alliance is essentially necessary to secure parliamentary victory.

There are now 120 parties operating in Turkey, up from 71 in June 2018 when the transformation of the political system from a parliamentary to a presidential one has become effective. The rise in new parties began as a trickle - two new political parties were established in 2018, while three new parties were formed in 2019. In 2020 alone, 27 new parties were formed, and another 17 have been formed so far this year.

While some of these parties - Democracy and Progress Party (DEVA), Future Party, Victory Party, and Homeland Party - can be seen in the polls, many of them remain unknown. These obscure parties have names that few in Turkey would have heard - such as the Love and Respect Party, the Light of Justice Party, the Ascension Party, and the Turkey Golden Age Party.

Public opinion researcher and political communication specialist Dr. İbrahim Uslu said that there is no rational reason for the explosion in the number of parties, especially in the past few years. The 50+1 rule, which gives the party that earns 50% of the vote an automatic majority, should disincentivize the splintering of the vote into smaller parties. However, he suspects that the rise in parties is related to the alliance system and a desire to push the opposition over that 50% mark.

Parties that could not make it into parliament given the 10% threshold, Uslu says, are likely hoping to make it into the body as part of an alliance. But there is one problem with that strategy - in order to become part of an alliance, a party needs to “have the qualification to stand for election.” Many of the newly established parties lack that qualification.

“It is then necessary to ask the question: If you did not get the qualification to participate in the elections, and if you are not taking any action even though being qualified takes quite a lot of effort, why did you establish a party?” Uslu said.

Uslu further suspects that the explosion in parties may have less to do with electoral practicality and more to do with disenchantment with the extant political system.

“It may have to do with the unhappiness caused by existing parties, the fact that politics excludes too many people, and it’s hard to find a place for these people in politics,” he said.

However, this does not solve the problem of the parties being unqualified to enter elections or engage in political activity, Uslu said.

“There is no effort to provide [political or electoral representation],” he said. “That is why there is no clear answer to this.”

Political Scientist Özgün Emre Koç, unlike Uslu, points directly to the establishment of the presidential system for the reason behind all of these new parties.

“The fact that the gradual weakening of the presidential government system can be easily observed by society has caused different social and political segments to set in motion some preparations and political plans. In other words, people predict that something is going to change in Turkey - they now see politics as an area where they can mobilize their own worldview,” he said.

He pointed to the 50+1 rule, unlike Uslu, as a reason behind the rise of these new parties. Even if they cannot all qualify, the fact that parties can only - in all likelihood - win through alliances means that even parties that can contribute an additional small percentage of the vote have gained importance.

“In this system, those who cannot get 50+1 percent cannot be elected alone,” Koç said. “This has brought alliances to the fore. Recent polls show that the gap between the People's Alliance and the Nation Alliance has narrowed. This has enabled parties that could bring 1%, 2%, or 3% of votes to be seen as more important. This gives small parties a serious say and makes them an alternative.”

Koç said there are also social reasons behind the rise in the number of parties. There has been a surge in politicization in Turkey in the past twenty years, but not many routes through which to direct this political fervor - civil society and means of expression have been quashed. Therefore, citizens are pushed to express their multipolar political views through elections and political parties.

“As different channels of participation in politics are blocked, people are directed towards a means of participating in politics that is directly focused on political parties and elections,” he said. “People may want to express themselves directly in the political environment.”

He predicts, however, that these parties won’t last long past a transfer of political power.

“As soon as the system changes in Turkey, most of the small parties will be nothing more than sign-on parties,” he said.

MHP to 'inform public about CHP-HDP alliance'Politics

MHP to 'inform public about CHP-HDP alliance'Politics Turkish citizens have no trust in Erdoğan’s government, poll showsPolitics

Turkish citizens have no trust in Erdoğan’s government, poll showsPolitics AKP considers changes to voting system: Electronic voting, fingerprints and no ballot envelopesPolitics

AKP considers changes to voting system: Electronic voting, fingerprints and no ballot envelopesPolitics