14 years on, justice remains as far as ever in Hrant Dink murder case

Friends and family of slain journalist Hrant Dink are still seeking justice in the case into his murder, with authorities having no intention to solve the crime. "Even though there were information and intelligence regarding the plans to kill Dink, the authorities didn't adopt the necessary protective measures, didn't carry out an operation against the organization planning the murder and paved the way for Dink's killing," Hakan Bakırcıoğlu, Dink family's lawyer, told Duvar English.

Neşe İdil / Duvar English

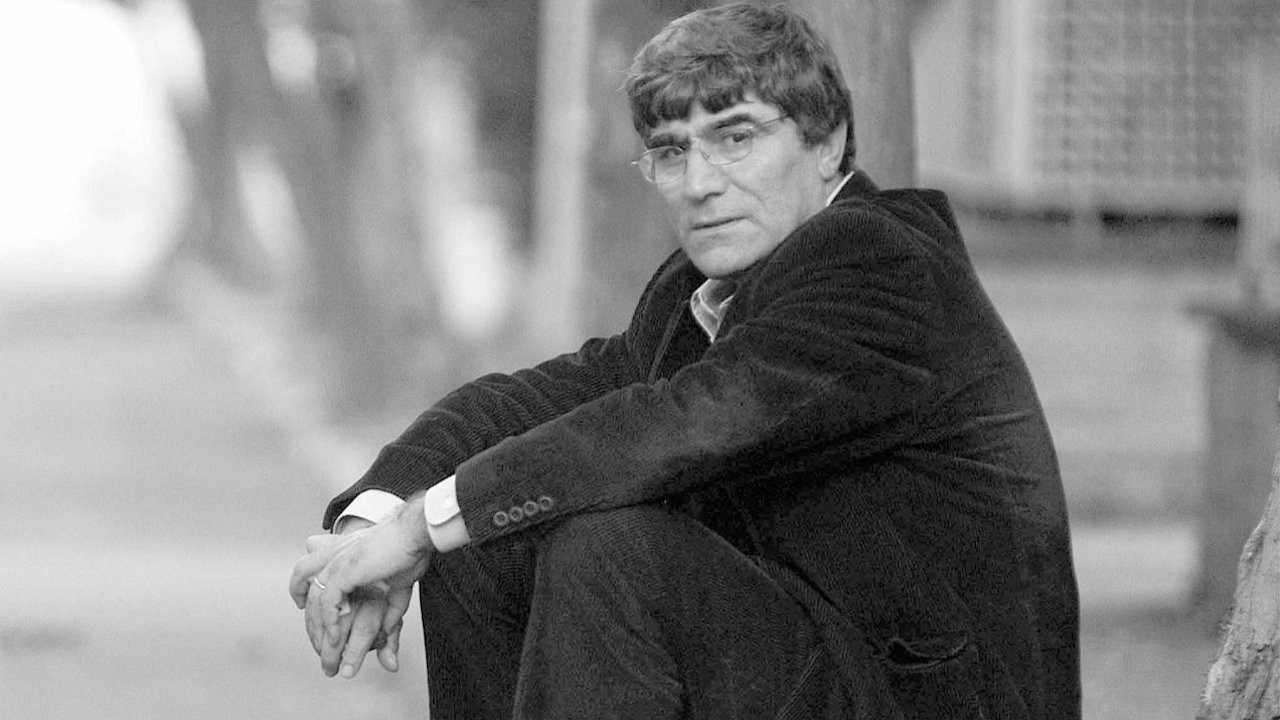

It was fourteen years ago today that 52-year-old Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink was murdered in broad daylight in central Istanbul. The murder, which remains unsolved to this day, sheds a harrowing light on the deep state and how Turkey perceives its Armenian citizens.

Dink, who was the editor-in-chief of Turkish-Armenian weekly Agos, was shot dead outside his office in Şişli by then 17-year-old Ogün Samast on Jan. 19, 2007. The path to his murder, however, dates way back, according to the Dink family's lawyer.

"There was an increasing atmosphere of threats against Hrant Dink that began in 2004. Even though there were information and intelligence regarding the plans to kill Dink, the authorities didn't adopt the necessary protective measures, didn't carry out an operation against the organization planning the murder and paved the way for Dink's killing," lawyer Hakan Bakırcıoğlu told Duvar English.

#HrantDink A life without justice. We miss him. https://t.co/BmpUNPCnJi

— HrantDink Foundation (@HrantDinkFnd) January 16, 2021

Dink, who was known for openly and genuinely discussing the issues surrounding the Armenian community in Turkey, became the target of the state even before 2004.

"One of the first steps to halt his influence on the public was taken in 2002 over his remarks at a symposium, where he said, 'I'm not a Turk, I'm a Turkish citizen and an Armenian.' He was sued for 'insulting Turkishness' for that," Bakırcıoğlu said.

The following year, a tip-off was received regarding an armed attack against Dink in Sydney during an event being underway and this tip-off was conveyed to Turkish police's intelligence units and the National Intelligence Organization (MİT) by the Turkish Foreign Ministry.

Turkish General Staff targets Dink

On Feb. 22, 2004, the Turkish General Staff released a press statement that targeted Dink over a report he penned on Sabiha Gökçen, the adopted daughter of Turkey's founder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, being an Armenian. According to the military, Dink's claims were "unhealthy" and "dangerous," hence calling on the related authorities to act.

The General Staff then asked then-MİT chief Şenkal Atasagun to arrange a meeting with Dink, which was followed by Atasagun ordering MİT Istanbul chief Hüseyin Kubilay Günay to meet with the journalist.

Günay and then-Istanbul Governor Muammer Güler decided that the meeting should be held between deputy governor Ergun Güngör, MİT's Istanbul terror branch head Özel Yılmaz and an official, identified only by the initials as H.S., and Dink. It took place on Feb. 24, 2004 in the Istanbul Governor's Office.

Dink would later describe the meeting as an attempt to "teach him a lesson."

"Güngör told Dink that 'people on the streets' pose a threat against him, while Özel warned him that he would draw public reaction," Bakırcıoğlu said.

'Insulting Turkishness' accusation

Two days after the meeting, a group chanted racist slogans in front of Agos offices in Şişli and personally targeted Dink. While a series of criminal complaints were filed by various individuals and institutions against Dink in the upcoming days, death threats also started to become frequent.

In 2005, Dink was convicted of "insulting Turkishness" following a series of hearings that were marred by racist slogans against him, as well as attempts of physical assaults. His sentence was approved by the Court of Cassation on May 1, 2006.

"This accusation means racism and I didn't commit such a crime. This is a black mark being tried to be put on me," Dink said at the time.

Another "insulting Turkishness" case was filed against Dink and his son Arat Dink over the former's remarks on the Armenian Genocide during an interview with Reuters in 2006.

"Of course I'm saying that it's a genocide because its consequences show it to be true and label it so. We see that people who had lived on this soil for 4,000 years were exterminated by these events," Hrant Dink told Reuters on July 14, 2006, which was followed by the said accusation in September.

'I'll just live with more fear'

The trial was carried out in circumstances similar to the previous one - racist slogans against Dink, attempts to physically assault him and countless media reports targeting the journalist.

"A lynch process began in 2004 and the lynching continued intensively until Jan. 19, 2007 when the murder took place," Bakırcıoğlu said.

"Dink started to be called a 'registered enemy of the Turks' and bunch of other insults following his conviction. This assured those planning the murder that the atmosphere is ripe for it," he added.

Dink was aware of the country's political atmosphere, the lynching process and threats against him, Bakırcıoğlu said, adding that the journalist penned a number of pieces on the issue between 2004 and Jan. 19, 2007.

"The people around me fear for my safety. And what about me? I can't say that I'm not afraid. But I'm not going to leave my country and flee. I'm used to living like this. I'll just live with more fear. That's all," Dink said in a piece dated March 5, 2004.

Two weeks prior to his murder, Dink penned a piece titled "Beginning a tough year," in which he said that 2007 would be a very difficult year in terms of political tensions in the country.

He also drew attention to the fact that state actors outside the political scene were seeking to provoke tensions and that trials against him may begin once again since the Armenian issue was on the country's agenda.

'On the edge of the same cliff once again'

On Jan. 12, 2007 - a week before his murder - he penned a piece titled "Why was I chosen as a target?" detailing the attacks, threats and court cases against him, concluding with the racist protests in front of Agos and the criminal complaint filed against him by a group led by a lawyer named Kemal Kerinçsiz.

"It was the start of a dangerous process. In fact, I have walked on the edge of danger throughout my life. Either danger loved me or I loved it; and here I was, on the edge of the same cliff once again," Dink said.

"There were people after me again. I could sense them. And I knew very well that they were not limited to Kerinçsiz’s group, that they were not that visible, not that ordinary," he said.

A week later, Dink was murdered.

Dozens of officials were aware of the plot

"All units of the state were aware of the attacks and threats against Dink that started in 2004," Bakırcıoğlu said.

In fact, the 14-year-long and never-ending judicial process showed that plenty of state officials were long aware of the assassination plan, but did nothing to stop it from being carried out.

Then-governor Güler knew about what was happening during the hearings and then-Istanbul police chief Celalettin Cerrah was aware of the threats against Dink.

"During the investigation and the hearings, state officials whose testimonies were taken as either suspects or witnesses said that Dink was among the 'potential targets.' The following process showed that they had concrete information that Dink was going to be murdered," Bakırcıoğlu said.

Documents showed that police and gendarmerie officers in the Black Sea province of Trabzon, where the killing was plotted, and security officials in Istanbul and Ankara knew about the plan to kill Dink.

Some 10 years after the murder, Istanbul Chief Public Prosecutor's Office on May 10, 2017 prepared an indictment that said the officials from the gendarmerie commands of Trabzon and Istanbul not only failed to stop the killing but actually were involved in it.

Two important documents

Two documents prepared by officials from Trabzon police and gendarmerie command were very significant in terms of the investigation and trial into the killing, Bakırcıoğlu said.

The document prepared by Trabzon police showed that police's intelligence department and Istanbul police were sent a notice on Feb. 17, 2006, which clearly stated that Yasin Hayal, who carried out a bomb attack in 2004, served time in prison, had radical ideas and hated Armenians, was planning to carry out an attack against Dink. The other document prepared by the Trabzon Gendarmerie Command revealed that Hayal organized the murder and provided the weapon, while Samast committed it.

"So, even though authorities had concrete information that Dink was going to be killed by Yasin Hayal 11 months before the murder, no measures to protect Dink was adopted," Bakırcıoğlu said.

While the indictment of 2017 is significant in terms of proving the state's responsibility in the killing, it could have been done ten years earlier, the lawyer said.

Barriers to not try state officials

The Istanbul Chief Public Prosecutor's Office didn't prepare an indictment against the state officials on April 20, 2007 even though it accessed the related documents that proved state involvement. It, instead, prepared an indictment against 18 individuals, including ultranationalist informant Erhan Tuncel, who was an asset of Trabzon police, Yasin Hayal and Ogün Samast.

The Trabzon Chief Public Prosecutor's Office prepared two indictments into eight officials from Trabzon Gendarmerie Command in 2007 and 2008, but only accused them of "neglection of duty."

In addition to totally ignoring the responsibilities of the Istanbul police, Trabzon police, Turkish national police, MİT and Istanbul Governor's Office in Dink's killing, and hence delaying their trials, the prosecutor's offices intentionally formed barriers to not try state officials.

In reports prepared by the Prime Ministry Inspection Board and Presidential State Supervisory Board on Oct. 10, 2008 and Feb. 2, 2012, respectively, extensive evaluations were made regarding state officials' responsibilities in the crime.

Top Europe rights court rules for rights violation

All the while, lawyers of the case took it to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), which on Sept. 14, 2010 ruled that Dink's right to life was violated on the grounds that officials were aware of the plan but didn't act and that no effective investigation was launched into those responsible.

Despite two reports by the boards and the ECHR ruling, the resistance towards investigating and trying state officials was not broken, Bakırcıoğlu said.

"We have filed plenty of criminal complaints to the Istanbul Chief Public Prosecutor's Office and asked for the scope of the investigation to be widened since 2007," the lawyer said, adding that their appeals against non-prosecution decisions yielded results.

Three separate rulings, including one from the Constitutional Court, were issued in 2014 that paved the way for the state officials to be investigated in relation to Dink's murder. Only after these, investigations were launched into the officials by Istanbul Chief Public Prosecutor's Office and their testimonies as suspects were started to be taken.

Two indictments were prepared in 2015 and 2017 and the trial of 77 individuals, mainly intelligence officials, gendarmerie and police officers from Istanbul, Trabzon and the Black Sea province of Samsun, began in Istanbul 14th Heavy Penal Court in 2016.

The scope and limits of the case

While it was an important step that an indictment was prepared against the state officials involved in Dink's killing, the Istanbul Chief Public Prosecutor's Office failed to investigate the organizers of the attacks that led to the murder.

"There was a direct connection to the events that led to the killing and the murder itself," Bakırcıoğlu said, while noting that a non-prosecution decision was given for suspects Veli Küçük, Kemal Kerinçsiz and Oktay Yıldırım even though their roles were apparent.

Another fault of the prosecutor's office was to not look into the archives of the institutions in question and to settle with the answers given by the suspects and their institutions.

"A significant portion of the state officials responsible for Dink's murder was involved in carrying out the investigation," Bakırcıoğlu said.

"Officials from the Istanbul Governor's Office and MİT officials in Istanbul and Trabzon weren't investigated. An indictment wasn't prepared against some of the officials of the Istanbul Police Department and national police," added the lawyer.

But the most important of all, Bakırcıoğlu said, is that the way and by whom the murder was decided was not completely revealed.

"Our objections were denied and the Constitutional Court in 2019 didn't rule for rights violations on these issues," he said.

"The way that the investigation is carried out by the Istanbul Chief Public Prosecutor's Office and the decisions for non-prosecution determined the scope and the limits of the case, making it impossible for a wholesome trial to be held."

Court rejects to hear intel officials

The trial that began in 2016 was overseen by a number of different court boards due to the changes in the court heads and judges.

"While our demands were taken into account by previous court boards, the attitude was reversed with the latest change in the court board," Bakırcıoğlu said, adding that the current board revoked a previous decision to hear MİT officials as witnesses and rejected the lawyers' objections.

"We told the court that the decision to not ask MİT officials for information would lead to the thought that the aim is to not clarify all aspects of this murder in this trial," he said.

Another demand rejected by the court board was to reveal why the army sought to meet with Dink in 2004.

Saying that a number of other demands were rejected by the court, Bakırcıoğlu noted that the court case was referred to the prosecutor for the preparation of an opinion and that the process of collecting evidence was terminated as a result.

"We are saying that the ruling of the court, which openly revealed that it won't try all aspects of the murder, won't be satisfactory neither for us, nor for those following the case," Bakırcıoğlu said.

The final defense arguments will be heard on Jan. 22.

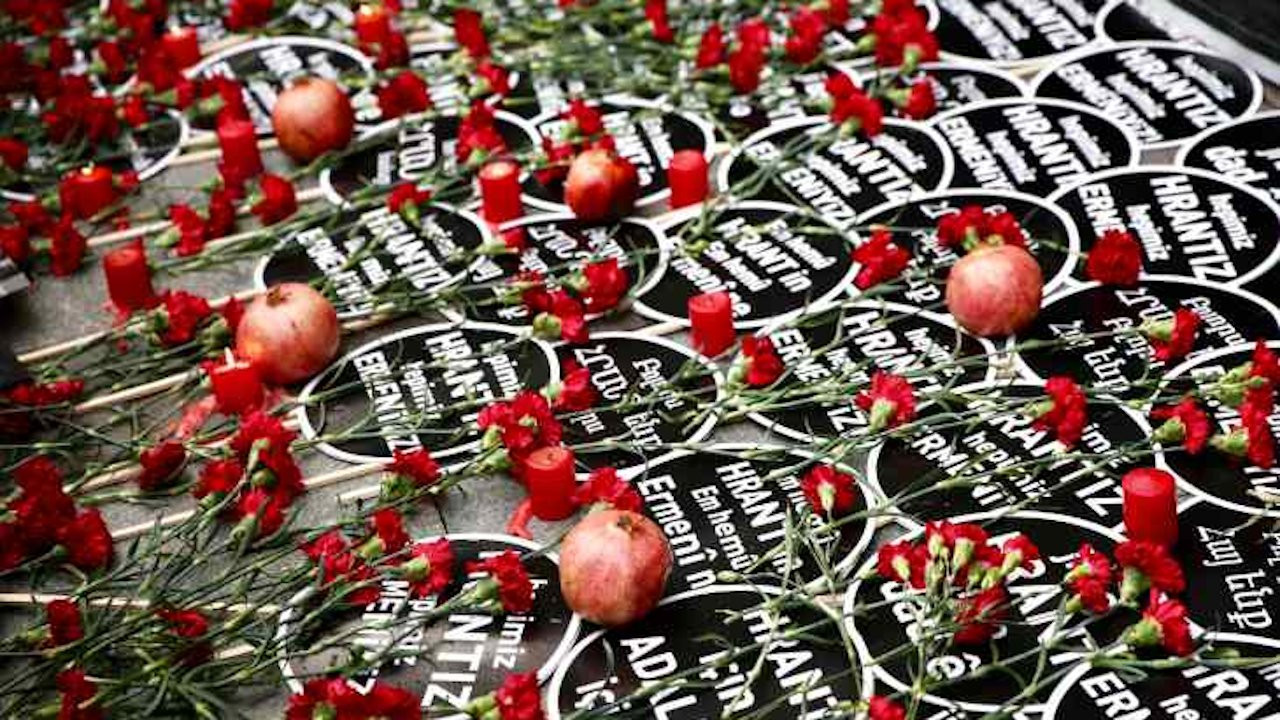

'We are here Ahparig'

As thousands commemorate Hrant Dink today by saying "We are here Ahparig," which means "brother" in Armenian, justice remains as far as ever. Images of doves are projected onto the façade of the former Agos building, where the journalist who devoted his life to peace was murdered, in reference to the metaphor in his very last article.

"I am just like a dove. Like a dove’s, my gaze flits right, left, forward, back. My head is just as fidgety, and quick to turn.

The accusations will continue, and new ones will come forth. Who knows how many injustices I will have to endure. But as these things happen, I will find reassurance in the fact that, while I may view my current state of mind, my current state of soul, as being marked by the disquiet characteristic of doves, I know that in this country, nobody ever hurts doves.

Doves live their lives in the hearts of cities, amid the crowds and human bustle.

Yes, they live a little uneasily, a little apprehensively—but they live freely too."

From tonight until January 19th from 18.00 (GMT+3) on doves will be accompanying Sebat Building, Istanbul. #YouAreHereAhparig #HrantDink pic.twitter.com/ZpDHTy6V3h

— HrantDink Foundation (@HrantDinkFnd) January 17, 2021

Armenians most targeted by hate speech in Turkish media, report showsHuman Rights

Armenians most targeted by hate speech in Turkish media, report showsHuman Rights Mafia leader says he was ordered to kill Hrant DinkHuman Rights

Mafia leader says he was ordered to kill Hrant DinkHuman Rights HDP demands parliamentary inquiry to shed light on Hrant Dink's murderHuman Rights

HDP demands parliamentary inquiry to shed light on Hrant Dink's murderHuman Rights