Khashoggi's inner circle targeted with Pegasus spyware before and after his death, leak reveals

NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware was used to secretly target the smartphones of those close to Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, according to digital forensic analysis.

Duvar English

In the wake of the brutal murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi, the NSO Group emphatically denied that its government clients had used its hacking malware to target the journalist or his family.

“I can tell you very clear. We had nothing to do with this horrible murder,” Shalev Hulio, the chief executive of the Israeli surveillance firm, told the US TV news programme 60 Minutes in March 2019. It was six months after Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist, was killed in Turkey by assassins dispatched by Saudi Arabia, a client of NSO.

Now a joint investigation by the Guardian and other media, based on leaked data and forensic analysis of phones, has uncovered new evidence that the company’s spyware was used to try and monitor people close to Khashoggi both before and after his death.

In one case, a person in Khashoggi’s inner circle was hacked four days after his murder, according to peer-reviewed forensic analysis of her device.

The investigation points to an apparent attempt by Saudi Arabia and its close ally the United Arab Emirates to leverage NSO’s spy technology after Khashoggi’s death to monitor his associates and the Turkish murder investigation, even going so far as to select the phone of Istanbul’s chief prosecutor for potential surveillance.

Khashoggi was killed and dismembered at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in October 2018. While the investigation mostly points to Khashoggi’s close associates being targeted in the months after the murder, it also identified evidence suggesting that an NSO client targeted the phone of his wife, Hanan Elatr, several months before his death, between November 2017 and April 2018.

'What can you do?'

The client appears to have used NSO’s spyware, Pegasus, which can transform a phone into a surveillance device, with microphones and cameras activated without a user knowing.

A forensic examination of Elatr’s Android phone found that she was sent four text messages that contained malicious links connected to Pegasus. The analysis indicated the targeting came from the United Arab Emirates, a Saudi ally. However, the examination did not confirm whether the device had been successfully infected.

“Jamal warned me before that this might happen,” Elatr said. “It makes me believe they are aware of everything that happened to Jamal through me.” She added that she was concerned his conversations with fellow dissidents might have been monitored through her phone. “I kept my phone on the tea table [in their Virginia home] while Jamal was talking to a Saudi guy twice a week.”

Elatr’s number was also contained in a leak of numbers that were selected by clients of NSO as candidates for possible surveillance. Access to the leak was shared with the Guardian and other media by Forbidden Stories, a nonprofit organization, as part of a collaborative investigation called the Pegasus project. Examination of phones was done by Amnesty International’s Security Lab, a technical partner on the Pegasus project.

U.S. intelligence agencies have already concluded that the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, was responsible for ordering the murder of Khashoggi, a former Saudi government insider whose criticism of the kingdom’s regime in the pages of the Washington Post was seen as a threat to the Saudi heir.

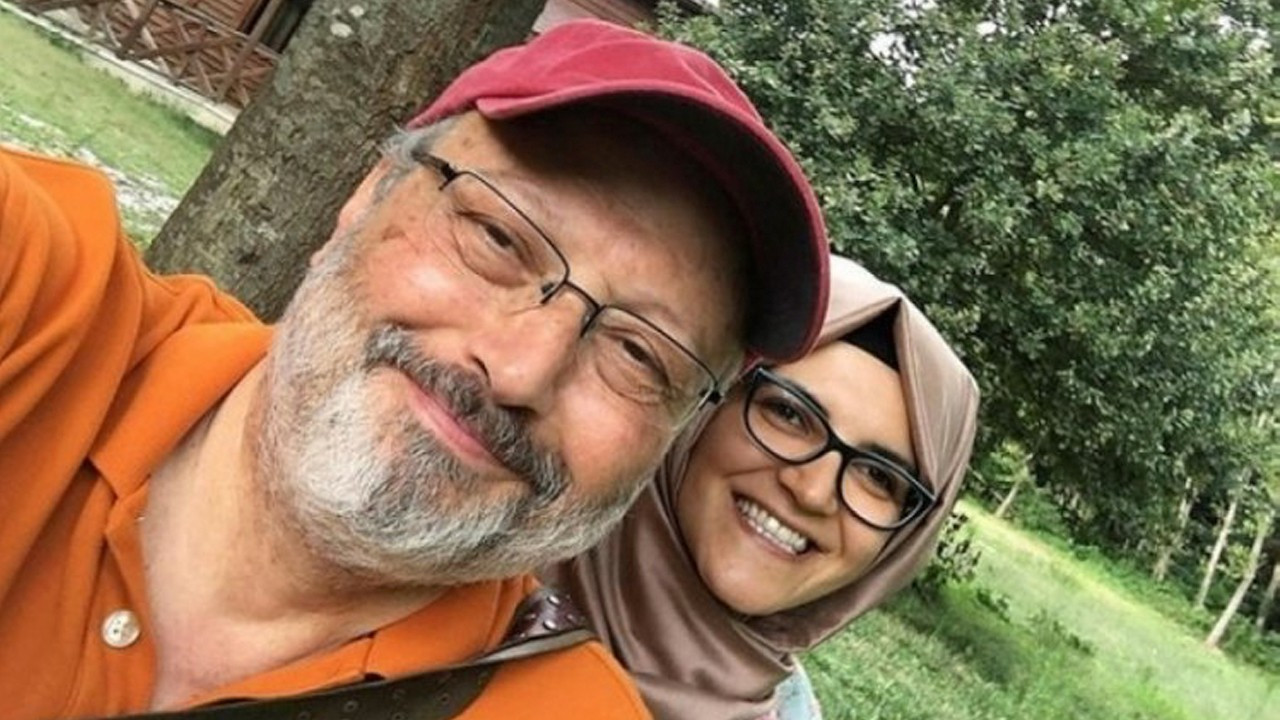

A team of Saudi agents killed Khashoggi inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul during his visit there to pick up documents he needed to get married to his fiancee, Hatice Cengiz, who later became an outspoken advocate for accountability over his murder.

Forensic analysis revealed that Cengiz’s phone was first infected with Pegasus just four days after his murder, on Oct. 6, 2018. Her phone was also hacked on two other days in October 2018. Further attempts to hack her phone followed in June 2019, although they did not appear to be successful. Data analysis suggested that Saudi Arabia was behind her hacking. Cengiz said she was not surprised she had been hacked: “I was thinking this after the murder. But what can you do?”

A close friend of Khashoggi, Wadah Khanfar, the former director general of the Al Jazeera television network, was also hacked using Pegasus, with analysis showing that his phone was infected as recently July 2021.

The phone analysis discoveries and leaked phone records suggest that Saudi Arabia and its allies used NSO’s spyware in the aftermath of the murder to monitor the campaign for justice led by friends and associates of Khashoggi, while also showing an intent to spy on the official Turkish inquiry into his murder.

Khashoggi associates who were targeted for possible surveillance after his death, according to the leak, include Abdullah Khashoggi, the journalist’s son; Azzam Tamimi, a Palestinian-British activist and friend, and Madawi Al-Rasheed, a London-based scholar who co-created an opposition party of expatriate Saudis in the wake of the murder.

Analysis of Rasheed’s phone found evidence of an attempted hack in April 2019, but there was no evidence the spyware was successfully installed.

Attempts to create a map of the journalist's connections

Other Khashoggi-connected names linked to in the data were Yahya Assiri, a UK-based Saudi activist who documents human rights violations in Saudi Arabia and was in close contact with Khashoggi before his death, and Yasin Aktay, a friend of Khashoggi and a top aide to the Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. No forensics were able to be carried out on their phones.

In an interview, Aktay said he had already been alerted by Turkish intelligence officials that his phone had been hacked after Khashoggi’s death because the Saudis were still trying to create a “map” of the journalist’s connections. “It was needless,” Aktay said of the surveillance. “I was just a friend of his.”

The phone number of İrfan Fidan, the Istanbul chief prosecutor who later formally charged 20 Saudi nationals over the killing, also appeared in the list of numbers of possible candidates for surveillance by NSO Group clients.

Without forensic examination of their phones, it is not possible to know whether these targets were infiltrated or successfully hacked using Pegasus.

In a statement, NSO said: “Our technology was not associated in any way with the heinous murder of Jamal Khashoggi. We can confirm that our technology was not used to listen, monitor, track, or collect information regarding him or his family members mentioned in your inquiry.”

Agnès Callamard, the secretary general of Amnesty International, which is a partner in the Pegasus project, said new discoveries about Khashoggi-related targets indicated an attempt by Saudi Arabia and others to gather intelligence on the fallout from the killing.

“The targeting indicates a clear intention to know what the prosecutor and a few other high political actors were doing,” she said. “They saw Turkey as the heart of what they needed to control.”

Turkish FM Çavuşoğlu in Saudi Arabia for talks to mend ties, end boycottDiplomacy

Turkish FM Çavuşoğlu in Saudi Arabia for talks to mend ties, end boycottDiplomacy Khashoggi's fiance wants 'punishment' for prince following US reportHuman Rights

Khashoggi's fiance wants 'punishment' for prince following US reportHuman Rights In change of tone, Turkey welcomes Khashoggi trial in Saudi ArabiaDiplomacy

In change of tone, Turkey welcomes Khashoggi trial in Saudi ArabiaDiplomacy Saudi de facto ruler approved operation that led to Khashoggi's death: USHuman Rights

Saudi de facto ruler approved operation that led to Khashoggi's death: USHuman Rights