Pandemic learning increases stress, anxiety for Kurdish-speaking students

Distance learning due to the Covid-19 pandemic has exposed the inability of Turkey’s education system to meet the needs of students whose mother tongue isn’t Turkish, say prominent educators.

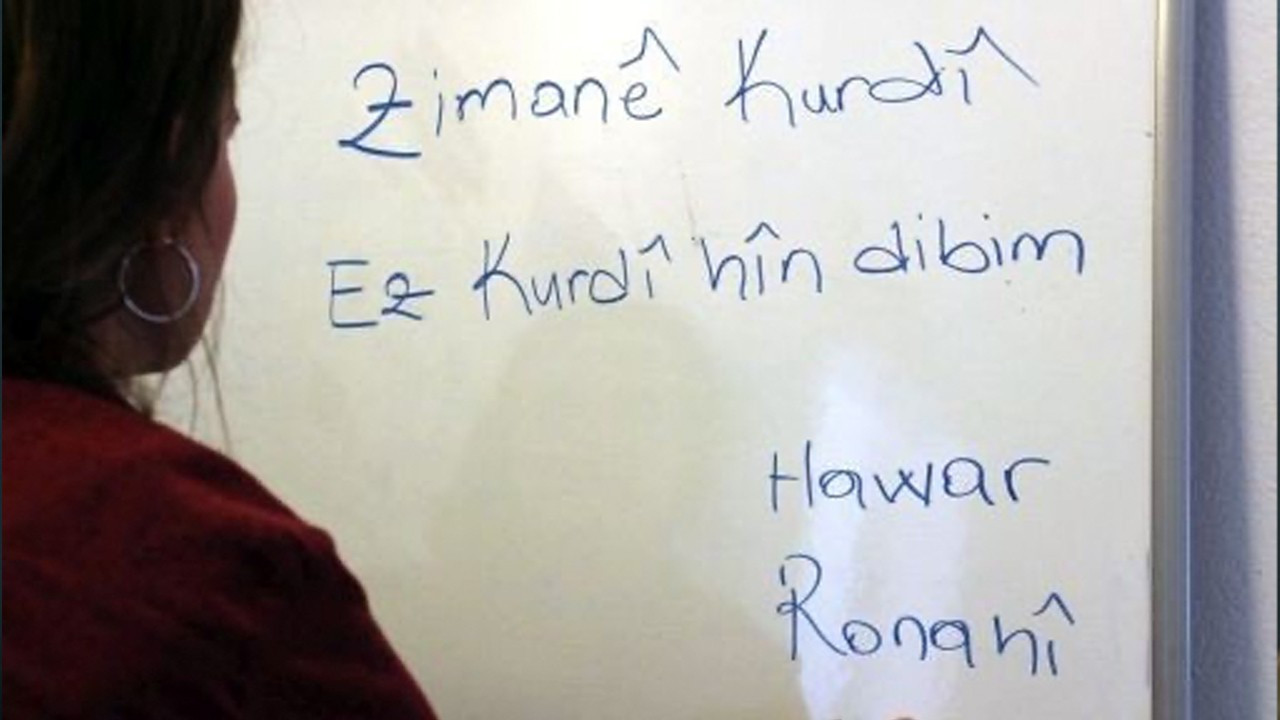

Ferhat Yaşar / DUVAR

As Turkish public schools open for the first time in eighteen months, Kurdish children whose first language is not Turkish are facing unique obstacles. Many of these students were unable to attend online classes after schools closed in March 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and have therefore been away from both school and Turkish language instruction for the past year and a half. Now, without support, millions of Kurdish students have been put at a unique disadvantage as they re-enter the classroom.

The issue of Kurdish language education has a long history in the Turkish educational system. After the foundation of the Turkish Republic in 1923, education in any language other than Turkish was banned and in the original version of the current constitution - passed after the 1980 military coup - Article 42 stated that “Aside from Turkish, no other language shall be studied by or taught to Turkish citizens as a mother tongue in any language, teaching, or learning institution.”

This ban was repealed by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP)-led government in 2004, but since the ending of peace talks between the Turkish government and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in 2015, Kurdish language education has again seen a decline.

According to educator Cemil Güneş, author of “Bilingual Children and Education,” the difficulties Kurdish students will face this fall cannot be separated from the politics surrounding the Kurdish issue in Turkey.

“The right to education in your mother tongue and the fact that a problem has been made of this right is not independent of the problem experienced by someone shot for speaking Kurdish on the street or humiliated for speaking Kurdish on a television channel,” he said.

Güneş, who was not allowed to study in his native language of Kurdish, has long studied the issue of students unable to study in their mother tongue and says that these children experience trauma and troubles far beyond the classroom. The education process, he says, begins in infancy and extends into social and public life. Children made to speak Turkish in the classroom may struggle socially as well as in daily life.

“The [educational] process begins when the child emerges from infancy and joins social life,” he said. “Due to language bans, these children face many problems not only at school, but also in the before and after school period. They even face these language bans at home, outside, on the playground, and at the market.”

When these children experience an interruption in their education - such as due to the Covid-19 pandemic - they are left to face all of these troubles on their own.

“These children and their families are standing helplessly before us,” Güneş said.

According to Güneş, the pandemic and the interruption in education it caused have revealed many of the broader issues with educating children in a language other than their mother tongue.

Educating children in a second language is linked with a range of academic issues, including academic failure, inability to read, lack of cognition of written work, and inability to understand and evaluate written texts.

They may also experience social phobia, have a tendency to violence towards themselves, be exposed to violence by others, be socially withdrawn, and have trouble speaking fluently. For children, these issues can cause significant trauma, which in turn can cause broader societal trauma.

“Families leave behind their mother tongues for their family’s and children’s safety, they distance themselves from societal and cultural memory, they leave the cities they live in, and in the face of all of this they have trouble speaking the language we call the ‘second language,’” Güneş said.

If these children were educated in their mother tongue, Güneş says, studies have shown that they would experience a feeling of belonging in the education process, a higher rate of productivity, and psychological relaxation.

They would also, likely have improved reading-writing and speaking-listening skills. Instead, these children during the pandemic have not only had to study in a second language, but have had to do so from afar with tablets and computers (if and when they had access). That has lead to millions of Kurdish children entering, for example, the second grade without the requisite literacy skills from first grade, said Güneş, leaving them “semi-lingual”.

Without proper support, they will only be left further and further behind and less fluent in both languages they speak.

“In recent years, the rate of speaking Kurdish among children has decreased,” said Güneş, “The fact that families have stopped speaking Kurdish among themselves and with their children worsens the process of semi-linguisticism. On top of that, the difficulties and inequalities experienced during the pandemic process make this process inextricable.”

Child psychiatrist Dr. Veysi Çeri further underlined the difficulties experienced by children whose first language is not Turkish. He says that the system - both pre- and post-pandemic - needs to be designed to meet the needs of these students so as to not cause them undue stress.

“There are many children in Turkey who have Kurdish or Arabic as their mother tongue, who speak these languages at home, and who only communicate in these languages until they start school,” Dr. Çeri said.

“This must be taken into account when these children start their education…otherwise, these children suddenly leave home and are exposed to a language they don’t know, which can increase stress. It can also increase children’s reluctance to, anxiety towards, and insecurity in school.”

Dr. Çeri says that in this critical, post-pandemic moment the educational system should be redesigned to incorporate bilingual education with a pedagogical approach that takes into account the experiences of students who do not speak Turkish. The system as it exists can cause children to experience extreme stress, which in turn causes trauma, which can cause deeper psychological and social issues later in life. Instead, the system needs to be adapted to these students and teachers need to help children learn.

“The strict prohibition, intolerance and punishment of the languages spoken by children in schools cause an increase in anxiety and insecurity in children…It is a very serious trauma when you cannot express yourself,” said Dr. Çeri.

Kurdish language education sees decline since collapse of peace process, says reportCulture

Kurdish language education sees decline since collapse of peace process, says reportCulture Disadvantaged Diyarbakır students create computers from paperSociety

Disadvantaged Diyarbakır students create computers from paperSociety Turkey's remote education system leaves behind Kurdish students in southeastEducation

Turkey's remote education system leaves behind Kurdish students in southeastEducation