Turkish Republic’s test with alcohol in its second century

It seems that alcohol will continue to be among the main problems of the Republic in its second century. Alcohol consumers need to be as brave and persistent as the political Islamists who do not hesitate to insult drinkers and take their money through taxation in the second century of a secular Republic.

Recently, the country's largest rakı producer celebrated the foundation of the centennial of the Republic with a stylish event. The event was held in Cité de Péra, today known as Flower Passage (“Çiçek Pasajı”), which was founded in 1876 by Hristaki Zoğrafos, one of the richest people of the period. Most of the guests who attended the event were figures from the world of culture, media and gastronomy. While the guests were listening to Jehan Barbur, Güvenç Dağüstün and Cem Adrian, they had fun realizing that the glasses of rakı they could (at least still) hold in their hands were an achievement of the Republic. I believe that the meaningful opening speech of the company manager and the meticulous content design of the event contributed greatly to this realization.

At the end of the event, hundreds of “ladies and gentlemen of the Republic” quietly headed home. It was a beautiful event, but it was celebrated behind black curtains stretched across the door of the huge Passage. Exactly 100 years later! Although it is understandable that the company making the invitation made such a choice for security reasons, I was thinking about the dimensions of the issue beyond security while returning home. How should we understand the increasing polarization that occurs in the environment we live in?

Exactly 100 years after the foundation of the Republic, the tension between political Islamists, who have created a legitimate ground to curse those who drink alcohol, and secularists, who are proud of drinking and being able to drink, is accumulating enough energy to resemble the North Anatolian Fault line. The accumulated energy is literally waiting to be released through the fractures. How can the point reached in a 100 years be perceived as a gain for some and as a dangerous period for others? Maybe we can find the answers in the summary of a hundred years of Republic and alcohol.

Were people able to drink alcohol in the Ottoman Empire?

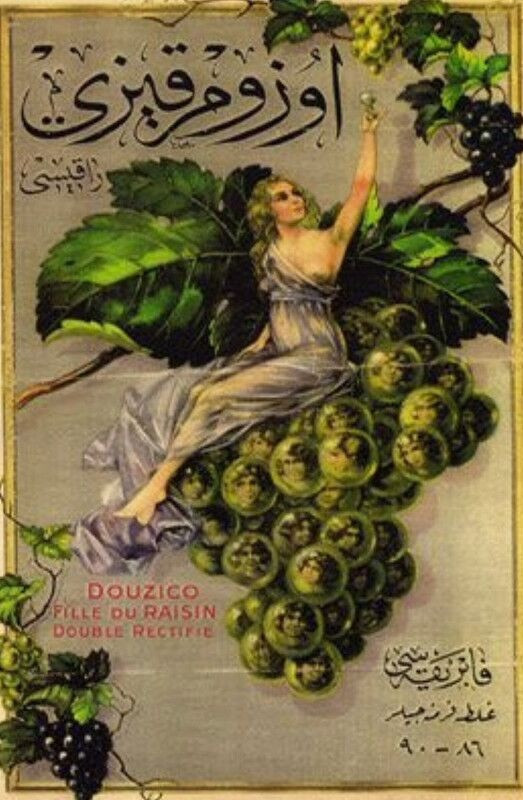

Even though our concern is the Republic, let's start by rewinding the issue much further back. We know that in the pre-Islamic period, Turks consumed drinks such as kumiss, wine and araki comfortably and abundantly both in daily life, in entertainment such as wedding ceremonies and in state diplomacy. Sources say that alcohol was consumed without taboos in the Ottoman Empire until the Sunni interpretation became dominant after the adoption of Islam. This continued until the Ottoman Empire disappeared from the stage of history. Even though alcohol is allowed for non-Muslim citizens and visitors, Muslims also have continued to enjoy the taste of life in these lands, both secretly and openly.

There is even a sultan nicknamed Drunken Selim. Finance Minister Sarıcazade Ragıp Pasha, the chief chamberlain of Abdulhamid II, who was very much loved by the Islamists, opened the first rakı factory. While alcohol was consumed among the palace and the subjects, the state administration tried to balance the budget with the revenues coming from alcohol. The ulama, as always, were eager to eradicate alcohol and drinkers.

The First Assembly, established on April 23, 1920, consisted of the two groups: One was dominated by revolutionary radicals, and the other was dominated by conservatives. The fact that the fourth bill on April 28, exactly five days after the foundation of the parliament, was about the alcohol ban can be considered the first seed of the tension that would last a 100 years.

The Prohibition Law proposal came into force with an interesting vote on Sept. 14, 1920, as a result of great controversy, delay tactics and fights. There were 71 votes in favor and 71 against. Konya deputy Mehmed Vehbi Efendi, a religious scholar and a strict conservative, voted in favor of the ban. Although it is not emphasized in the sources why Mustafa Kemal did not attend this session, it is abundantly stated that he did not comply with the prohibition imposed by the law.

Perhaps our story is the story of the conflict between those who want to guide science and remove alcohol from being a taboo and those who have dreamed of a religion-based, conservative and alcohol-free society since those days when the Trabzon deputy Ali Şükrü Bey, who brought the proposal, was killed by Mustafa Kemal's bouncer Topal Osman.

Istanbul, the capital of alcoholic beverages, meets the Republic

The western İzmir province, where most of the entertainment venues, producers and regulars were Greek, lost almost all of its liquor stocks in the fire that broke out immediately after it was taken over by the Kemalists. The alcohol ban had begun for İzmir. Istanbul, on the other hand, continued its relationship with alcohol freely until Oct. 8, 1923. Istanbul facing a strict alcohol ban in the days that coincided with the foundation of the Republic was caused by the Kemalists who opposed the ban. This situation should not be a strange irony of history. The new Turks, the owners of the New Republic, had to put everything in order. Being a nation state required this. Greeks, Armenians and Jews had to comply with the new order, and capital owners had to accept these new partners. If not voluntarily, forcefully.

From alcohol ban to state monopoly

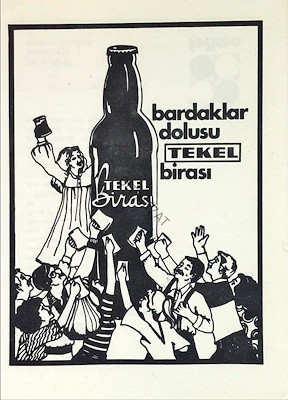

By 1924, the caliphate was abolished, the new country was turned towards a secular route, and the alcohol ban was also ended. Alcohol became free, but the tax on alcohol was quadrupled. As an indicator of the seriousness of the state, the first step towards state monopoly was taken by establishing a new administration in 1926. After these years when the private sector was still able to produce rakı, a period of complete monopoly began with the establishment of the General Directorate of Monopolies in 1932. In 1944, the production was completely taken over by the state and TEKEL (“Monopoly”) company as we know it was born. Until 2003, TEKEL meant alcohol.

Post-TEKEL period and the AKP rule

Of course, we did not know that the years when the state monopoly on alcohol was abolished were the years when we set out towards a new state order. In those years, no one thought of reading the issue in this way and could not. Now, a significant part of the country is trying to breathe under the weight of the disproportionate and relentless taxes imposed on alcohol by political Islamists. Despite these negative conditions, the number of alcohol producers and the amount of consumption is increasing day by day. Entertainment venues and taverns are gaining reputation again. Even Michelin stars are brought to the country by the state.

On the other hand, music, entertainment and alcohol bans that started during the pandemic are being expanded at every opportunity. Efforts are being made to completely prevent drinking in parks and public spaces. The new order is trying to be established, in which drinking alcohol is prohibited, those who drink it are infidels, and those who allow it are abettors.

Although it may seem like a paradox, the AKP, like the Ottomans, cannot give up the money coming from alcohol. They fuel the hatred of their own conservatives by symbolizing controversial issues such as alcohol. Of course, they don't care about the lumpenization caused by this strategy. They don't care that we have turned into a barren country without alcohol, entertainment and art. As long as they do not lose the order they have established (but have never been able to establish).

In short, it seems that alcohol will continue to be one of the main problems of the Republic in the second century. In that case, it is necessary to name the problem by its name. Alcohol consumers need to be as brave and persistent as the political Islamists who do not hesitate to insult drinkers and take their money through taxation in the second century of a secular Republic. Perhaps they need to lift all the curtains.