At all 62 public hospitals in Istanbul, no Kurdish translation offered

At 62 public hospitals in Istanbul, English and Arabic translations are offered, but not Kurdish. As a result, many patients from Istanbul’s large Kurdish population are turned away without treatment.

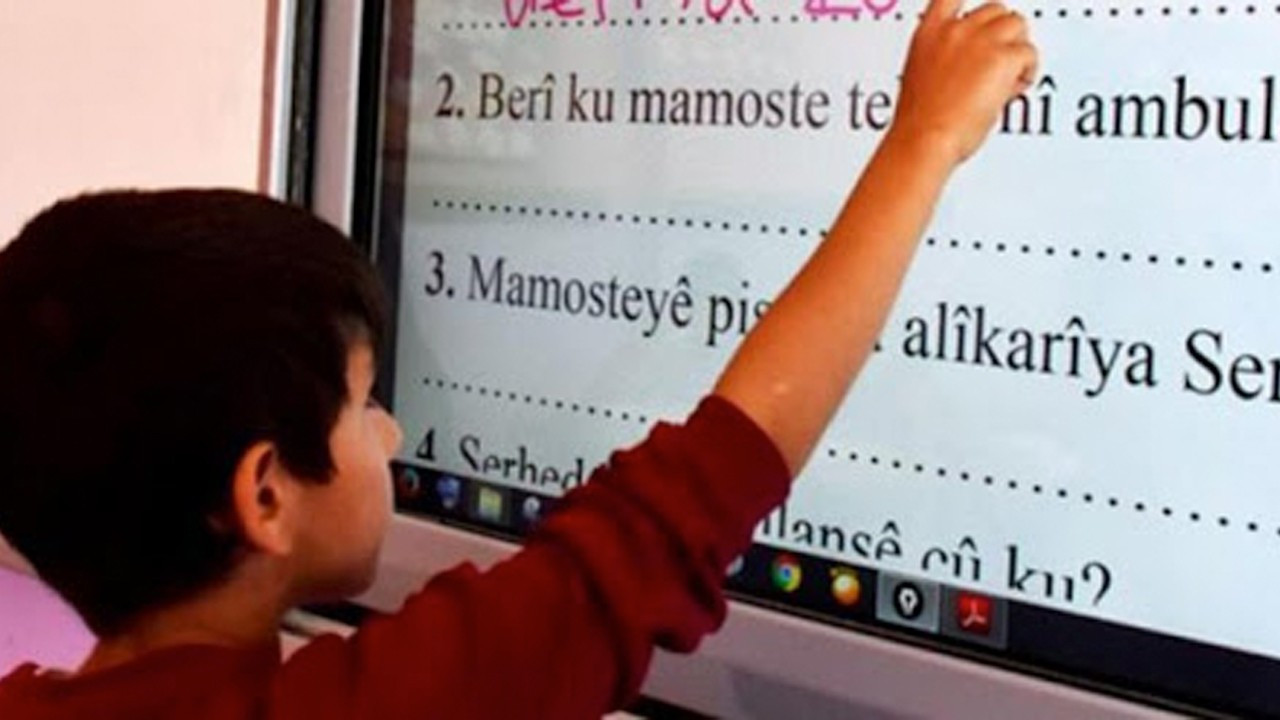

Ferhat Yaşar / DUVAR

Istanbul, the largest city in Turkey, is home to one of the country’s largest Kurdish populations. Millions of Kurdish people migrated to the city from the country’s east, especially in the last fifty years, for a variety of reasons, including work, economic opportunity, and fleeing violence. Despite this, of Istanbul’s 62 public hospitals, none of them offer Kurdish translation for patients.

Kurdish language rights have long been contentious in Turkey. Kurdish language use was banned in public institutions, such as schools, after the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923. After the 1980 military coup, the use of the Kurdish language in public was banned entirely - that ban remained in place until 1991.

At the beginning of its tenure, the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) loosened many restrictions on Kurdish as part of the so-called "Kurdish Opening", but since the collapse of peace talks with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in 2015, repression of the Kurdish language has again been on the rise.

This repression extends to the medical sphere, and the effects of this are particularly felt by Kurdish women. Many Kurdish men, as a result of socializing, work-life, and public life, are more fluent in Turkish. However, women, especially those who remain at home, are less exposed to Turkish - in their homes, they primarily speak Kurdish. As a result, when they need medical care for themselves or their children, they are often unable to access it.

The challenges faced by these women begin long before they go to the hospital. For those not experienced in the use of computers and the internet, it is impossible to book a medical appointment on the state central appointment system (MHRS). Then, when they try to use the call center to book an appointment, they are unable to speak to an operator in Kurdish. Many of these women are forced to rely on their children, family, and friends to access care.

The problem worsens when they arrive at the hospital, often alone. Many spend hours trying to find a doctor who can speak Kurdish. Those that do consider themselves “lucky” - they remember that doctor’s name and go to them repeatedly. Those that don’t have to explain themselves with broken Turkish, gestures, and indications to the part of their body that is ailing them. Often, without a proper diagnosis, doctors write these patients strong prescriptions and send them away. However, without understanding what the directions on the box say, many of these patients turn to herbal remedies instead and are afraid to return to the hospital.

At the four hospitals with the most patients in Istanbul - Haseki Training and Research Hospital, Şişli Hamidiye Etfal Training and Research Hospital, Taksim Training and Research Hospital, and Okmeydanı Training and Research Hospital - there are translators who speak Arabic and English, but not Kurdish. As a result, report employees, many Kurdish patients who come to these hospitals end up leaving without seeing a doctor. They wait for someone with whom they can communicate, but if that person does not come, they leave.

“Sometimes we don’t have colleagues who speak Kurdish and so patients end up waiting,” one hospital employee said. “They [patients] go away after a while. There are so many patients who speak Kurdish; a hospital employee who speaks Kurdish needs to be placed here. This needs to happen in every single hospital.”

Dr. Murat Ekmez, who works at Haseki Training and Research Hospital, said that of the brochures provided to the hospital by the Health Ministry, not a single one is in Kurdish. He said that not only is this a threat to the patient, but also to the institution of the patient-doctor relationship.

“The patient-physician dialogue is a very delicate one,” he said. “The state believes that we can communicate to the patient through their relatives […] This is a threat to patient and physician privacy. Maybe the patient wants to share something with us that they don’t want to share with their relatives. It would be much more comfortable for the patient to share this through a translator.”

This is especially relevant to obstetrics and gynecology, he said.

“The woman may not want to tell her relatives about a childbirth complaint. She might want to tell you something about her sex life. It is impossible for a person who comes with a relative to express this in front of them,” he said.

As a result of this inability to communicate, Dr. Ekmez added, patients receive inadequate care. They are sent away without doctors fully understanding their ailment, their symptoms, or its cause. Doctors do not understand the patients’ medical histories, which is critical to giving a proper diagnosis. Patients are misdiagnosed, misprescribed medicines, and often their illnesses do not ameliorate. Kurdish patients already experience discrimination in their daily lives for speaking Kurdish, and that discrimination extends to their medical care.

“An examination without [knowing medical history] is an incomplete examination,” Dr. Ekmez said. “A large community living in this country is being discriminated against.”

When Gazete Duvar asked the General Directorate of Public Hospitals and the Istanbul Provincial Health Directorate if they had plans to put in place Kurdish translators, or at least conduct research on how this was affecting patients’ medical care, the officials declined to comment.

Istanbul: A city that's accessible in 20 languages except KurdishHuman Rights

Istanbul: A city that's accessible in 20 languages except KurdishHuman Rights Civil society organization to launch online Kurdish language lessonsHuman Rights

Civil society organization to launch online Kurdish language lessonsHuman Rights Turkish Education Ministry dismisses Kurdish ethnicity of Diyarbakır, says residents speak AzeriDomestic

Turkish Education Ministry dismisses Kurdish ethnicity of Diyarbakır, says residents speak AzeriDomestic Kurdish Language Platform applies to UNESCO for recognition of mother languageHuman Rights

Kurdish Language Platform applies to UNESCO for recognition of mother languageHuman Rights