COVID-19 in Turkey: One year marred by rights violations, murky data

Turkey leaves behind one year of the COVID-19 pandemic, marking the first anniversary of Health Minister Fahrettin Koca's declaration that a patient had been diagnosed in the country on March 11, 2020. Since then, the country has suffered from extreme government opacity, rights violations under the guise of pandemic restrictions, and poor state management of the crisis that led to nearly 30,000 patients' death, not to mention healthcare workers.

Azra Ceylan / Duvar English

"I have a sad, but not scary, piece of news for you. One of our patients who was suspected to have coronavirus tested positive," said Health Minister Fahrettin Koca on March 11, 2020, fundamentally shifting the lives of millions in Turkey.

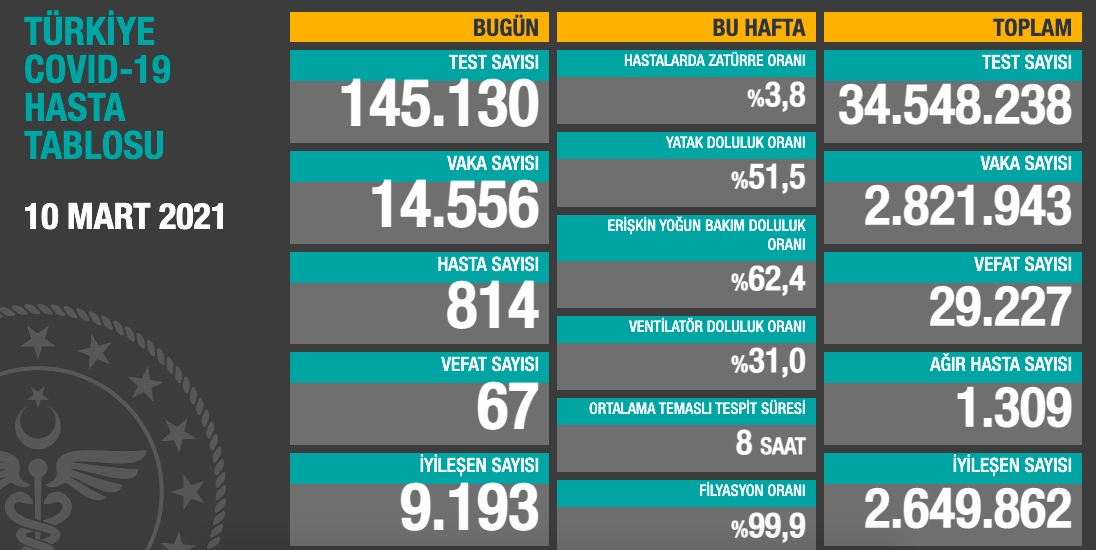

Exactly one year later, the country has counted nearly 30,000 deaths from the pandemic, and almost three million were infected with the disease, although these numbers remain suspicious, as the government has proven their lack of dedication to data transparency multiple times during the pandemic.

The Health Ministry revealed in the fall that they had only been reporting the number of symptomatic patients since July, confirming the public's fears that Turkey had prematurely relaxed COVID-19 restrictions in May.

After weekend lockdowns, mandated mask usage and travel restrictions in March and April, Turkey relaxed regulations in May, reopening malls and gradually permitting travel.

The relaxation of restrictions quickly caused COVID-19 numbers to skyrocket, with claims of 30,000 new patients diagnosed each day by medical associations in September, which eventually led the Health Ministry to reveal their distinction between symptomatic patients, which they called "patients" by the ministry, and asymptomatic patients, dubbed "cases."

Despite an increasing number of new patients dying and being diagnosed each day, Ankara re-started in-person classes on Oct. 5 for about five weeks, after which the country went into alarm over the increasing number of cases being reported from all different regions.

After months of withholding the number of asymptomatic cases, the Health Ministry confirmed on Nov. 25 that the number of daily diagnoses was indeed near 30,000.

Restrictions on alcohol sales

On Nov. 30, Turkey went into a second set of restrictions, including some that were widely interpreted as interventions in citizens' personal lives, including a smoking ban in public places, restrictions on alcohol sales and curfews.

Turkey entered 2021 with an expectation for a massive shipment of Chinese CoronaVac shots and under a four-day curfew that was strictly enforced by Ankara to make sure no New Year's Eve celebrations were held.

The beginning of 2021 was also marred by dire human rights violations caused by increased political oppression from Ankara, fueled by protests against President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's appointment of a rector to Boğaziçi University on Jan. 1.

The Istanbul Governor's Office promptly issued bans on public demonstrations under the pretense of COVID-19 restrictions, although the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) scheduled mass provincial congresses for weeks before and after February.

Provinces where the AKP held superspreader events soon observed a spike in the number of COVID-19 cases, with attendees of the AKP events testing positive for the disease as well.

Ankara fails pandemic management test

Surveys conducted throughout the pandemic revealed that the public's confidence in Ankara's management of the pandemic increasingly dwindled, a process expedited by the Health Ministry's data opacity.

The Health Ministry also failed to distribute masks that were supposed to be delivered to all citizens free of charge, and medical experts often said that health workers were not given the resources to adequately protect themselves from the virus.

The government openly attacked the Turkish Medical Association (TTB) for correctly predicting that official numbers weren't accurate, with President Erdoğan's ally Devlet Bahçeli calling the organization "terrorists" and calling for their closure.

The government also saw internal political turmoil during the pandemic, as a resignation from Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu was "rejected" by the president.

Meanwhile, former Finance Minister and President Erdoğan's son-in-law Berat Albayrak released his unforeseen resignation on Instagram before dropping off of the political and public sphere entirely. Albayrak's whereabouts remain unknown as of March 11, 2021.

Dire rights violations

Ankara also sanctioned rights violations during the pandemic by passing unjust legislation, instructing police brutality and legal measures taken to silence critics.

In a probation law that aimed to alleviate overcrowding in prisons to diminish the risk of COVID-19, Ankara allowed a mafia leader close to Bahçeli to be released, while making sure that all charges used to accuse critics were exceptions to the probation rule.

As the incarceration of Turkey's political prisoners continues, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has ruled for a second time, during the pandemic, that former co-chair of pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP), Selahattin Demirtaş's rights were violated by his extended imprisonment.

President Erdoğan said in response to the ECHR ruling that the European court didn't have a say over Turkish jurisdiction, while also calling Demirtaş a "terrorist."

Turkish gov't holds superspreader events, but uses pandemic as tool to silence criticsCoronavirus

Turkish gov't holds superspreader events, but uses pandemic as tool to silence criticsCoronavirus Pandemic-era burnout: Turkey's overworked doctors are quitting in dangerous numbersCoronavirus

Pandemic-era burnout: Turkey's overworked doctors are quitting in dangerous numbersCoronavirus Turkey ranks 74th out of 98 countries in COVID Performance IndexCoronavirus

Turkey ranks 74th out of 98 countries in COVID Performance IndexCoronavirus Turkey reports over 40,000 cases of COVID-19 variantCoronavirus

Turkey reports over 40,000 cases of COVID-19 variantCoronavirus COVID-19 cases on rapid rise across Turkey amid normalization effortsCoronavirus

COVID-19 cases on rapid rise across Turkey amid normalization effortsCoronavirus