Social media activism: doomed with it, doomed without

Last week, Turkey was rocked by appalling news about a case of child abuse in the province of Antalya. The case involves a mother and stepfather abusing and “selling” their children, two young siblings, so others can sexually abuse them. The thought of these abusers walking free outraged millions in the country. Many shared their thoughts on social media. Digital activism certainly has an effect, but we are repeatedly caught in the same cycle of atrocity-outrage-response.

Last week, Turkey was rocked by appalling news about a case of child abuse in the province of Antalya. The details can be readily found here, but it suffices to say that the case involves a mother and stepfather abusing and “selling” their children, two young siblings, so others can sexually abuse them. On June 29, it came out that the abusers were released pending conviction.

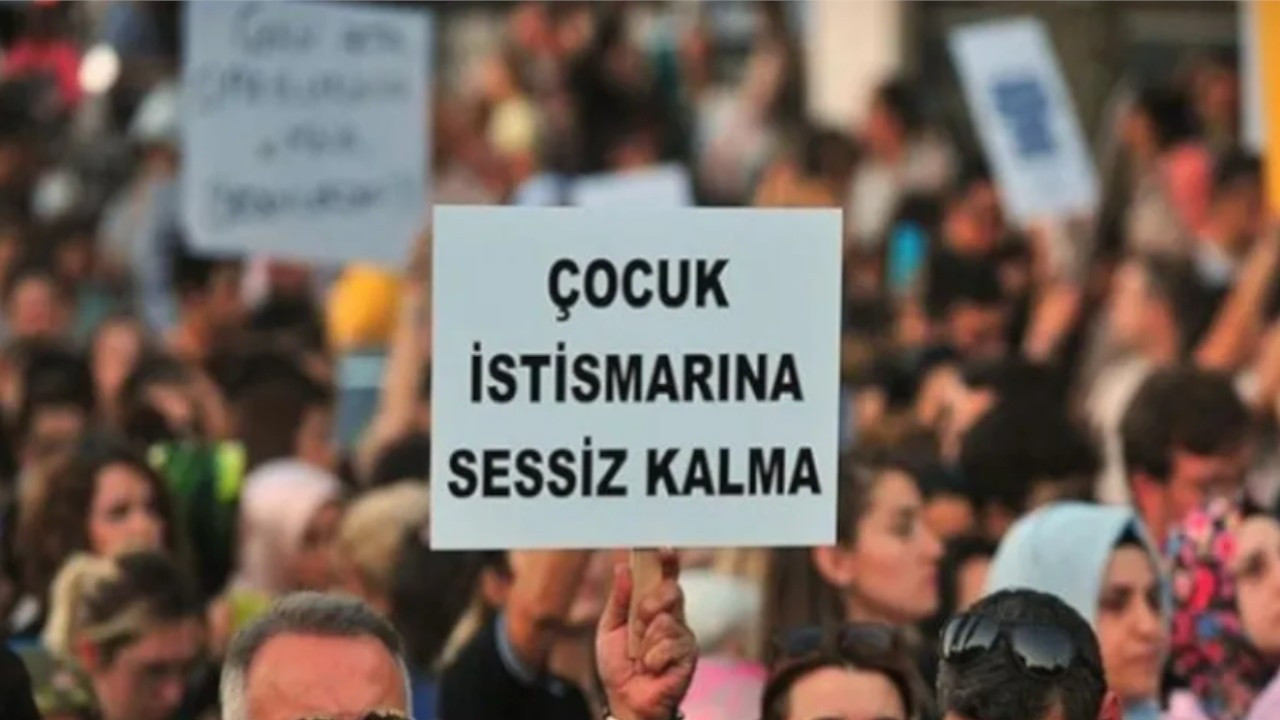

The thought of these abusers walking free outraged millions in the country. Many shared their thoughts on social media under the hashtag #ElmalıDavası, after the name of the district in Antalya where the events took place. Among those posted were famous actors and actresses like Kerem Bürsin, Hande Erçel, Mert Fırat and Demet Özdemir trying to draw attention to the case.

Pop star Tarkan also took to Twitter to express his disappointment and anger: "The case has shaken me and I cannot pull myself together. The Ministry of Family and Social Services said they were ‘following the case’ but this does not mean anything. We know that these are empty words and promises, as always. This will be another inconclusive case and no punishment will be served. The deviants will be left to walk free. We want action, we want results.”

This statement is bold and commendable. It is an example of someone with a massive platform using it for good. But why is it that we have to learn about the intricacies of the legal system’s approach to child abuse from a pop star? Something has gone seriously wrong with Turkey’s courts and laws when everyday citizens are required to become amateur legal experts just to comprehend the mess being made around them.

For instance, the news of Elmalı Case broke as the government announced its latest legal amendments as part of the ominously named “Human Rights Action Plan.” What do these changes to the legal system do for human rights? It requires that “concrete evidence” be provided in cases of child abuse, torture, sexual assault, and so on.

Yet one of the key pieces of evidence proving abuse in the case of the Elmalı siblings was stick-figure drawings the children made detailing their abuse. Under these new legal changes, a child’s own verbal or written statements about their abuse will not be sufficient to arrest the perpetrator. According to groups like the Federation of Women Associations of Turkey, this requirement for “concrete evidence” will increase the number of abusers who go without punishment. An abused child is not easily able to video record or otherwise document their own abuse. To expect such a thing can only mean that you are not serious about preventing abuse.

I am no legal expert, but as a concerned person who lives in this country, I am forced to educate myself on what is happening and to speak out against it. Unfortunately, social media is one of the only routes we have left for expressing our outrage. One of the social media posts that resonated with many was from the Instagram account “Turkish Dictionary.” The account began a couple of years ago with cheeky explanations and literal translations of colorful Turkish idioms. Today with over 800,000 followers, the account is mostly focused on raising awareness about injustices in the country. The account’s creators are aware of the irony of an Instagram humor page becoming an influential place where people get news about important issues like child abuse or homophobia in the country.

In the Turkish Dictionary post on the Elmalı Case, one graphic had the message “Why do we have to search for justice on social media?” This sentence was written over and over in white on the same slide. The implicit message is something like this: It’s horrible enough that children are being abused in this country, but why is it that to see the perpetrators punished we regular citizens are forced to use our social media accounts to force the courts to do their job?”

It’s a fair question. As much as social media is an echo chamber without much real-world effect, it’s also one of the few ways people in Turkey can intervene in politics. For example, it was only after the social media outrage about the child abusers being set free that the Ministry of Family and Social Services released their announcement about “following the case closely,” whatever that means.

And so digital activism certainly has an effect, but we are repeatedly caught in the same cycle of atrocity-outrage-response. Today the outrages have piled up so high that this strategy can clearly serve us no further. While this case of child abuse is being discussed, the new requirement for “concrete evidence” could cause thousands of abusers to be released from prison. To make matters even more urgent, on July 1, Turkey officially withdrew from the Istanbul Convention to prevent violence against women. And this comes after a week of police violence against LGBTQI+ people peacefully gathering in public to celebrate Pride.

Social media activism is not enough, but without it, we’re doomed. The streets are also not an easy option. The feminist and LGBTQI+ communities are not only online but protesting in public, but they are consistently beaten and arrested for it. And so where do we go from here?

After social media outrage, ministry puts two children sexually abused by parents under state protectionHuman Rights

After social media outrage, ministry puts two children sexually abused by parents under state protectionHuman Rights Turkish gov't seeks to pardon 480 inmates jailed over child sexual abusePolitics

Turkish gov't seeks to pardon 480 inmates jailed over child sexual abusePolitics